We fought for 33 years to abolish not proven verdict after our daughter's murder

David CowanScotland home affairs correspondent

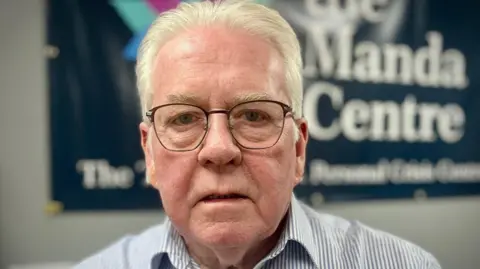

Duffy family

Duffy familyJoe and Kate Duffy were devastated and baffled when the man accused of their daughter’s murder walked free from court.

They had felt certain that Francis Auld would be found guilty of killing 19-year-old Amanda in Hamilton in 1992.

But a jury found the charges against him not proven – one of two verdicts of acquittal which could be returned in criminal trials in Scotland.

Joe and Kate did not initially understand what the jury’s verdict meant – and have now spent more than three decades campaigning for the abolition of not proven.

From 1 January, this centuries-old verdict has been consigned to the history books and Scottish trials will end with the accused being found either guilty or not guilty.

“There’s some solace in the fact that no other family will have to go through this,” said Kate.

“There’s relief and a feeling of vindication – but most importantly, it’s for our daughter. It’s for Amanda.”

Amanda had gone missing after a night out in her hometown of Hamilton in May 1992. Her body was found on waste ground the next day.

By any standards, the murder of the 19-year-old drama student had been exceptionally brutal.

Her numerous injuries included a bite on her breast which the defence agreed had been inflicted by Auld.

When the jury at the High Court in Glasgow announced the not proven verdict, Joe and Kate had no idea what it meant.

They listened in astonishment as the judge told Francis Auld he had been acquitted and was free to go.

Afterwards, in a side room, lawyers explained that in the eyes of the law, not proven was exactly the same as not guilty. Auld had been cleared and could never be tried again.

Kate fainted.

She was carried from the building on a stretcher and taken to hospital.

Joe said that throughout the case the police and prosecution had assured the couple that they had a very strong case and expected to get a guilty verdict.

“So when it was not proven, you were like, what exactly does that mean? There’s something wrong here.”

“It was the fear of knowing that the person who was responsible, in my eyes, was still out there and capable of doing it again,” said Kate.

A common interpretation of not proven was that the jury suspected the accused was guilty, but felt the prosecution had failed to prove the charge beyond reasonable doubt.

Good luck finding that in a law book. As Joe and Kate were to discover, there was no written legal definition of not proven.

Over the years, whenever juries asked, all judges could tell them was that it was a verdict of acquittal, just like not guilty.

Research has also shown that some people thought – incorrectly – that the accused could be tried again if the verdict was not proven.

That has been allowed in exceptional circumstances since 2011 under double jeopardy legislation, but the method of acquittal plays no part in that process.

Within weeks of the verdict in November 1992, Joe and Kate had set up a table in a street in Hamilton, gathering tens of thousands of signatures for a petition calling for not proven to go.

Joe explained: “I’ve never understood why you can have two verdicts which mean exactly the same thing.

“The only difference in law between not proven and not guilty is spelling.

“That’s it. Why do we need them? Either you’re guilty or not guilty.”

Hamilton’s Labour MP George Robertson believed some juries were using not proven as a “cop out” and put forward a private members’ bill at Westminster proposing abolition.

He failed to win the backing of the then Conservative government and not proven survived.

The Duffys regarded the bill’s failure as a stumbling block rather than a knockout blow. They set up a charity to help other families bereaved by murder, culpable homicide and suicide.

The beginning of the end

Ten years ago they established a counselling facility in Hamilton called the Manda Centre, the family’s nickname for Amanda.

It was a case in 2015 that finally signalled the beginning of the end for not proven.

A jury used it when they cleared a man accused of raping a student at St Andrews University.

The victim, known as Miss M, sued Stephen Coxen for damages in a civil court and won. The sheriff accepted she had been raped by Coxen.

It was said to be the first civil damages action for rape following an unsuccessful criminal prosecution in almost a century.

The outcome would have struck a chord with the Duffys. In 1995, Joe and Kate had sued Frances Auld over Amanda’s death and won damages – which were never paid.

A new campaign for abolition, led by Miss M and backed by Rape Crisis Scotland, argued that not proven was used disproportionately in sexual offence cases.

They said it offered juries “an easy out” and contributed to “guilty people” walking free.

Their case won support from leading politicians, including Nicola Sturgeon, who was first minister at the time.

In 2022, the SNP administration at Holyrood proposed a raft of legal reforms, including the removal of not proven.

Controversy over the verdict dates back to the mid-19th Century and the arguments for and against have changed very little over the years.

Critics said it was confusing for juries and the public, failed to provide closure for alleged victims, and stigmatized the person on trial by appearing not to clear them completely.

Supporters of the verdict argued that it was an important safeguard against wrongful convictions.

Scotland’s top lawyers – the Faculty of Advocates – put it this way: “The not proven verdict may be a safety valve for jurors who have not reached the threshold for conviction but reject the impossibility of guilt.”

But this time, abolition had cross-party support and not proven’s days were numbered.

The Scottish government’s bill was passed by MSPs September this yearwith Miss M and the Duffys watching from the public gallery at the Scottish Parliament.

In what was portrayed as a counter-balance, the legislation brought about another crucial change.

Scottish juries have 15 members. Until now, a guilty verdict could be returned through a simple majority – eight votes out of 15.

From today, a two-thirds majority will be required. At least 10 out of 15 jurors will have to support a conviction.

The Scottish government said there was clear evidence that jurors were more likely to convict if they only had a choice of guilty or not guilty, and the change would ensure the system was fair and balanced.

Prosecutors at the Crown Office and campaigners at Rape Crisis Scotland fear the change will make it harder to get convictions.

The Law Society of Scotland would have preferred the unanimity or near-unanimity required by the jury system in England and Wales.

It could be years before the consequences of all of this become clear.

In 2016, prosecutors sought permission to put Francis Auld on trial for a second time over Amanda’s murder, using the new double jeopardy law.

Their application was turned down by the courts. Auld died from cancer in 2017.

“The grief part, you learn to live with it,” said Kate. “You learn to live your life in a different way.”

The couple paid tribute to Miss M and the part she played in bringing about the end of not proven.

“I take my hat off to her because she’s really put herself out there,” said Joe.

“There have been an awful lot of false dawns along the way but we’ve never, never given up.

“So for anybody who wants to campaign for something to be changed, don’t stop, keep going for it.

“It might have taken us 33 years but you know something – we finally got there.”