The First Crusade: Holy War or Holy Hypocrisy?

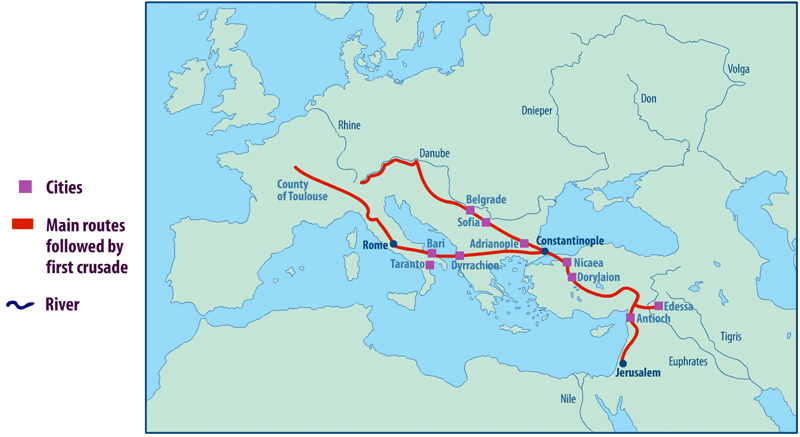

The First Crusade (1096–1099) is often remembered in church history as a sacred mission to liberate Jerusalem from Muslim control, clothed in the language of holy war and divine justice. Pope Urban II’s fiery words at Clermont promised forgiveness of sins and eternal reward for those who “took the cross,” while Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos portrayed himself as a desperate defender of Christendom in need of Western aid. Yet beneath these lofty claims lay political ambition, fear, and opportunism.

What unfolded was not the triumph of a just cause but a descent into hypocrisy and brutality. The “defenders of the faith” turned first on Jewish communities in Europe, then on their supposed Christian allies in Byzantium, and finally on Muslim, Jewish, and Eastern Christian populations in the Levant. The rhetoric of justice masked the greed of generals, the power struggles of kings, and the bloodlust of starving armies. From Baldwin’s treacherous rise in Edessa to the cannibalism at Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān and the wholesale slaughter in Jerusalem, the crusade repeatedly betrayed the very ideals of righteousness it claimed to uphold.

The First Crusade was less a holy war than a dark mirror of human ambition—religion weaponized to sanctify violence, and “just war” reduced to propaganda in the hands of men hungry for survival, wealth, and power.

Alexios I Komnenos and His Self-Preserving Appeal

By the end of the 11th century, the Byzantine Empire was in crisis. The humiliating defeat at the Battle of Manzikert (1071) had shattered imperial authority in Anatolia, leaving much of Asia Minor under the control of the Seljuk Turks. By the time Alexios I Komnenos seized the throne in 1081, the empire was shrinking, beset by Norman raids from the west, Pecheneg incursions from the north, and Turkish expansion from the east. The emperor’s position was precarious, and he knew that without reinforcements his rule could collapse altogether.

Alexios’s motives in reaching out to the West were not primarily spiritual but political. He dispatched envoys to Pope Urban II, meeting him at the Council of Piacenza in March 1095. The emperor requested not an army of peasants or zealots, but small contingents of disciplined Western knights to act as mercenaries under Byzantine command. These forces would serve his immediate strategic needs: to push back the Seljuks, secure Asia Minor, and stabilize his throne.

What Alexios did not anticipate was how his appeal would be reframed. The emperor had asked for carefully controlled reinforcements, but his request became the spark for a mass movement he could neither predict nor control. In place of a limited military alliance, he would be confronted with vast and unruly armies of crusaders whose presence often endangered Byzantium as much as it threatened the Turks.

Thus, the origins of the First Crusade were already marked by contradiction: an emperor who sought self-preservation through measured assistance ended up unleashing a wildfire of religious fervor and mob violence. Far from reflecting the “just war” ideal, Alexios’s request was the first step in a campaign where political survival was dressed in the clothing of divine mission.

Urban II’s Propaganda at Clermont

When Alexios appealed for help, he sought military reinforcements to defend Byzantium. But when Pope Urban II addressed the Council of Clermont in November 1095, he transformed that pragmatic request into a spiritual campaign unlike anything Christendom had yet seen.

Urban framed the expedition not as an act of political alliance but as a holy mission. He painted lurid pictures of Muslim rulers in Jerusalem desecrating holy sites and oppressing Christian pilgrims—stories that were at best exaggerated and at worst invented. In reality, under Muslim rule, Christians had lived in Jerusalem with relative freedom of worship for centuries. But propaganda served Urban’s purpose: he was not answering Alexios so much as he was mobilizing Western Europe under papal leadership.

The heart of his message was radical. Knights who had spent their lives shedding blood—often condemned to Hell for their violence—were told they could redirect their swords in the service of God. By fighting in the East, their sins would be forgiven, and eternal salvation assured. Urban’s speech inverted Christian teaching: violence, once a damnable sin, was now sanctified as the highest form of penance.

This was not “Just War” in the Augustinian sense—defensive, limited, and morally restrained. It was a carte blanche indulgence, a call for violence with heavenly reward attached. For the Pope, it was an opportunity to expand papal authority, to unify Christendom under Rome, and to channel Europe’s chronic violence outward rather than inward.

The Appeal to the Masses

The call of Clermont spread across Europe like wildfire. What Pope Urban II had intended primarily for knights and nobles was seized upon by peasants, artisans, women, and even children. Chroniclers describe entire villages stirred by fiery preachers, abandoning fields and families to “take the cross.” For many, the crusade was not a carefully considered act of just war but an emotional stampede born of desperation, poverty, and apocalyptic expectation.

The phenomenon became known as the “People’s Crusade.” Unlike the disciplined armies Alexios had hoped for, these were vast, untrained mobs, ill-equipped for long campaigns. They were driven less by strategy than by zeal—and, often, by hunger and opportunism. Preachers like Peter the Hermit fanned the flames, convincing common folk that joining the march was both holy duty and personal salvation.

This mass response undercut the very principle of just war. Augustine had argued that war must be waged by proper authority, for a just cause, and with right intention. But the crusade quickly became the opposite: a popular movement of ungoverned violence, fueled by promises of forgiveness and plunder.

As the first waves left Europe, it became clear that this was not the righteous army of God promised at Clermont, but a chaotic multitude, primed to unleash devastation wherever they went. The crusade was no longer a disciplined defense of Christendom but an unbridled eruption of mass violence sanctified by the Church.

The Slaughter of the Jews

If the First Crusade had been justified as a holy mission to liberate Jerusalem, its first victims proved otherwise. In the spring and summer of 1096, bands of crusaders, particularly those led by Count Emicho of Leiningen, turned their fury not eastward toward Muslims but inward upon Jewish communities in the Rhineland.

Mainz, Worms, Cologne, Speyer—centers of thriving Jewish life—were ravaged. Men, women, and children were slaughtered by mobs who believed they were purifying Christendom before setting out for the Holy Land. Some Jews were forced to choose between baptism and death; others were massacred outright. Estimates vary, but thousands perished in these pogroms.

Eyewitness Jewish chronicles testify to the desperation of the victims. Many, convinced that forced conversion was a fate worse than death, chose suicide rather than baptism. Parents, in heartbreaking scenes, even killed their own children to prevent them from falling into the hands of the crusaders. These actions, remembered as acts of martyrdom (kiddush ha-shem), underscore both the terror of the moment and the depth of religious conviction that sustained Jewish communities in the face of annihilation.

Church authorities, including some bishops, attempted to shield Jewish populations, but the crusaders often overwhelmed their protection. Pope Urban II himself neither endorsed nor decisively condemned the massacres, and the rhetoric of his crusade had already sanctified violence as penance. For many crusaders, killing Jews became part of their pilgrimage.

From the very outset, the crusade betrayed the core of “just war” theory. Instead of targeting military threats, crusaders attacked defenseless civilians. Instead of fighting under proper authority, mobs acted on zeal and bloodlust. The slaughter of the Jews exposed the crusade’s true nature: not a righteous defense of the faith, but a movement where religious justification masked unrestrained violence against the innocent.

Peter the Hermit: Zeal Without Restraint

Among the most charismatic figures of the early crusade was Peter the Hermit, a wandering preacher whose fiery sermons stirred the imaginations of Europe’s poor. Riding on a donkey and clothed in rags, Peter presented himself as a prophet of God’s will, claiming divine visions that commanded him to lead the faithful to Jerusalem. His simple message—that ordinary peasants, women, and even children could earn salvation by marching east—resonated far more powerfully than the measured appeals of nobles and bishops.

Yet Peter’s movement, later called the “People’s Crusade,” revealed the dangerous fusion of religious fervor and mob violence. His followers were largely untrained and poorly supplied, relying on pillage as they crossed Europe. In Hungary and the Balkans, they looted towns and terrorized locals. In Germany, some bands swept into Jewish quarters, joining in the massacres that stained the opening months of the crusade.

When the ragtag army reached Constantinople in the summer of 1096, Emperor Alexios I quickly realized the danger of their presence. Fearful they would destabilize his city, he ferried them across the Bosporus to Asia Minor, hoping to direct their zeal against the Seljuks. But without discipline, provisions, or leadership, Peter’s crusaders quickly collapsed into chaos.

In October 1096, near the town of Civetot, Seljuk forces ambushed the People’s Crusade. Tens of thousands were slaughtered in a single day. Chronicles report that the ground was littered with corpses, the sea choked with the bodies of those who had tried to flee by boat. Peter himself had already left the camp to negotiate supplies with Alexios; he survived, but his credibility as a leader was broken.

The legacy of Peter the Hermit’s crusade was not a holy march to Jerusalem but a trail of atrocities, pogroms, and a catastrophic massacre. His story revealed the hollowness of the crusading ideal: far from embodying just war, the People’s Crusade became an eruption of uncontrolled zealotry, sanctified by religious rhetoric but doomed by its own violence.

The Crusaders Converge upon Constantinople

By late 1096 and early 1097, the main armies of the First Crusade—far larger and better armed than Peter the Hermit’s mobs—began to arrive at Constantinople. These forces were led by some of Western Europe’s most prominent nobles: Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond of Toulouse, Bohemond of Taranto, and Hugh of Vermandois, among others. Yet even these “official” crusaders brought with them not only knights but also vast numbers of peasants, servants, and camp followers.

To Emperor Alexios I, their arrival was both a relief and a nightmare. He had hoped for a few thousand disciplined knights to shore up his defenses. Instead, he found himself confronted with tens of thousands of hungry foreigners, encamped outside his capital and demanding food, shelter, and payment. Far from strengthening Byzantium, they threatened to overwhelm it.

Alexios had little interest in their vision of a holy war. For him, the crusaders were mercenaries to be controlled, bound by oath, and deployed against his enemies. To prevent them from destabilizing his empire, he refused to let them enter Constantinople freely. Instead, he pressured their leaders to swear oaths of fealty, promising that any lands recaptured from the Muslims would be returned to Byzantine authority.

Tensions ran high. Many crusaders distrusted Alexios, seeing his caution as cowardice or betrayal. The emperor, for his part, regarded them with suspicion and contempt—undisciplined adventurers cloaked in religious zeal but ultimately driven by greed. His strategy was simple: push them away from Constantinople as quickly as possible, directing their energies against the Turkish-held city of Nicaea.

The Siege and Surrender of Nicaea (1097)

In May 1097, the crusading armies set their sights on Nicaea, the former Byzantine capital now held by the Seljuk Turks. The city was formidable: strong walls, tall towers, and a lake supplying provisions. For the inexperienced and malnourished crusaders, taking Nicaea by storm seemed nearly impossible. Siege engines faltered, and their attempts to scale the walls met with devastating counterattacks.

Despite their shortcomings, the crusaders’ sheer numbers and persistence alarmed the defenders. Yet it was not the crusaders’ bloodlust that decided the city’s fate, but the diplomacy of Alexios I. Determined to reclaim the city for Byzantium without letting his unruly allies sack it, Alexios secretly opened negotiations with the Turks inside. He offered them generous terms: surrender to Byzantine authority in exchange for their lives.

On June 19, 1097, the garrison agreed. At dawn, the crusaders awoke to find the banners of Alexios flying from Nicaea’s towers. Instead of glory, plunder, and vengeance, they were greeted with a fait accompli: the city had passed peacefully into Byzantine hands.

The crusaders were furious. They had bled, starved, and fought under the promise of holy war, only to be denied the fruits of victory by the very emperor whose cause they had supposedly taken up. Alexios’s refusal to let them loot the city was seen as betrayal, further souring relations between the Western crusaders and their Byzantine host.

The episode at Nicaea revealed the stark contrast between rhetoric and reality. For Alexios, the crusade remained a political tool, not a sacred mission. For the crusaders, the denial of plunder made clear that even among supposed Christian allies, the ideals of righteousness and unity were no more than masks for self-interest. With their frustrations boiling, the crusaders turned their march southward—not yet realizing that worse hardships, betrayals, and atrocities awaited them.

Baldwin and the Seizure of Edessa (1098)

As the main crusading host pressed southward, Baldwin of Boulogne—brother of Godfrey of Bouillon—broke away with a smaller contingent. His motives were clear: personal power and wealth. While the crusade’s official rhetoric was about liberating Jerusalem, Baldwin saw opportunity in the divided political landscape of the East.

In early 1098 he arrived at Edessa, a wealthy Armenian Christian city on the fringes of Turkish territory. The townspeople, weary of Muslim raids, initially welcomed the crusaders as protectors. Its ruler, Thoros of Edessa, an Armenian Orthodox leader unpopular with his subjects, hesitated but ultimately sought to secure his position by adopting Baldwin as his heir.

But Baldwin’s pious mask quickly slipped. Shortly after the adoption ceremony, Thoros was overthrown. Some sources suggest he was murdered by a mob incited by Baldwin’s supporters; others imply Baldwin himself engineered his foster father’s death. According to one account, Thoros was dragged to the roof of a fortress and hurled to his death. His severed head, placed on display, left no doubt that Baldwin now ruled in his place.

With Thoros gone, Baldwin proclaimed himself Count of Edessa—the first crusader state established in the East. What was justified as Christian solidarity against Muslim Turks was in truth a cynical act of usurpation, replacing one Christian ruler with another by means of betrayal and bloodshed.

The seizure of Edessa exposed the hollowness of crusader rhetoric. Baldwin had not fought Muslims for the defense of Christendom; he had manipulated an ally, usurped his throne, and set himself up as a feudal lord. The crusade, which had begun as a supposed war of justice and faith, was already producing fiefdoms carved out by treachery and ambition.

The Siege of Antioch (1097–1098)

After Nicaea and the march across Anatolia, the crusaders turned their attention to Antioch, a great city commanding the route to Jerusalem. The siege began in October 1097 and dragged on for nearly eight months. With supply lines stretched thin and reinforcements delayed, the crusaders descended into misery. Hunger gnawed at the armies, leading to desertions, infighting, and even atrocities among their own ranks.

Chroniclers describe scenes of shocking desperation. Crusaders reportedly drank the blood of their horses to stay alive. In the darkest moments, both Muslim and Christian sources accuse them of cannibalism—feasting on the bodies of the dead. Whether exaggerated or not, these accounts capture the savagery that consumed what was supposed to be a holy mission.

In June 1098, through treachery, a section of the city walls was opened by an Armenian guard sympathetic to the crusaders. Antioch fell, and the crusaders unleashed their fury. Contemporary accounts record the massacre of the city’s inhabitants—Muslims, Jews, and even Eastern Christians caught in the chaos. Women and children were not spared. Homes were looted, synagogues burned, and even churches were plundered. Sacred vessels, icons, and relics were seized as spoils, desecrating the very sanctuaries the crusaders had claimed to liberate.

Amid this chaos and sacrilege came a sudden “miracle.” With Kerbogha of Mosul’s relief army now besieging the crusaders inside the city, morale collapsed. Starvation, disease, and fear gripped the camp. At this desperate moment, a poor priest named Peter Bartholomew announced that he had received visions directing him to dig beneath the Church of St. Peter. After hours of excavation, a rusty spearhead was unearthed—the so-called Holy Lance that pierced Christ’s side at the crucifixion.

For a starving army, the lance was a godsend. Chroniclers like Raymond of Aguilers celebrated it as proof of divine favor. The relic was paraded through the camp, carried into battle, and became the banner of a miraculous breakout. When Kerbogha’s divided coalition faltered and fled, the victory was hailed as supernatural confirmation of the crusading cause.

But even at the time, many doubted its authenticity. Adhemar of Le Puy, the papal legate, remained skeptical, and others suspected the spear had been planted to manipulate morale. Indeed, the discovery fit a pattern: throughout the crusades, “holy relics” seemed to appear at opportune moments, serving as propaganda to justify conquest and sanctify plunder.

The conquest of Antioch revealed the crusade’s deep contradictions. It was marked by cannibalism, indiscriminate slaughter, the desecration of churches, and the exploitation of relics as psychological weapons. Bohemond’s seizure of the city for himself, in defiance of his oath to Alexios, sealed the hypocrisy. Antioch was hailed as a victory for Christ, but in truth it exposed the crusade as a war driven by desperation, greed, and ambition, thinly cloaked in the language of righteousness.

The Atrocity at Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān (1098)

Fresh from the ordeal of Antioch, the crusaders pressed south toward Jerusalem. In December 1098, they besieged the Syrian town of Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān. The city resisted for weeks, but when its defenses finally collapsed, the crusaders stormed in with fury.

What followed was not a victory of liberation but a massacre. Contemporary accounts—both Christian and Muslim—agree that the crusaders slaughtered the town’s inhabitants without distinction. Men, women, and children were cut down. Muslims, Jews, and even Eastern Christians perished alike in the frenzy. Streets were filled with corpses, homes were burned, and survivors were enslaved.

Worse still, the famine that had plagued the crusading army turned the massacre into something darker. Chroniclers record that the crusaders not only killed indiscriminately but also resorted to cannibalism. Albert of Aachen writes that they “boiled pagan adults in cooking-pots, impaled children on spits, and devoured them grilled.” Muslim historians such as Ibn al-Athir confirm similar horrors, describing crusaders roasting the flesh of the dead. Even crusader eyewitnesses like Radulph of Caen admitted to eating human remains, though he excused it as desperate necessity.

This atrocity left a stain on the crusade that even contemporaries could not ignore. What Pope Urban had proclaimed as a holy mission had devolved into scenes more horrific than anything attributed to their Muslim foes. The crusaders’ actions at Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān exposed the utter collapse of the just war framework: civilians were massacred, holy purpose was abandoned, and starvation became a justification for barbarism.

The episode also revealed how far the crusaders had strayed from their original cause. Instead of marching with zeal to Jerusalem, they lingered in plunder, consumed by infighting and demoralization. Their leaders quarreled over spoils and titles, while their armies devoured the very bodies of those they had sworn to liberate. The “holy war” had become an orgy of violence, a nightmare cloaked in the language of salvation.

The Sack of Jerusalem (1099)

After three years of famine, infighting, and bloodshed, the crusaders finally reached their ultimate goal: Jerusalem. In June 1099, they laid siege to the holy city, then held by the Fatimid Egyptians. After weeks of grueling assaults, on July 15, the crusaders breached the walls. What followed was a slaughter so vast it horrified even contemporaries.

Eyewitnesses describe the massacre in chilling detail. The Gesta Francorum, a Latin chronicle, records crusaders “walking in blood up to their ankles.” Raymond of Aguilers, another crusader chronicler, described rivers of blood flowing through the streets. Muslim accounts, such as those of Ibn al-Athir and Ibn al-Qalanisi, confirm the wholesale killing of the population. Jews, who had taken refuge in their synagogue, were burned alive when the crusaders set it aflame. Muslims were cut down indiscriminately. Eastern Christians, too, were killed in the chaos, their churches desecrated along with mosques. Men, women, and children—all were victims.

The sack of Jerusalem was hailed in the West as divine victory. A day after the conquest, crusaders marched barefoot in solemn procession to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, singing hymns of thanksgiving. Yet their prayers rose over a city littered with corpses and blackened with fire.

The leaders of the crusade claimed their reward. Godfrey of Bouillon refused the title of “king,” styling himself instead Advocate of the Holy Sepulchre, but he ruled Jerusalem as its de facto monarch. Within days, the crusaders established the Kingdom of Jerusalem—the crown jewel of the crusader states.

But behind the rhetoric of liberation, the conquest of Jerusalem exposed the final hypocrisy of the First Crusade. It was not a war of justice but of annihilation. Its climax was not the defense of the innocent but the indiscriminate slaughter of thousands. If Urban had promised remission of sins through holy war, Jerusalem proved instead that sins were multiplied beyond measure.

The bloodbath of July 1099 was not the triumph of Christian justice but the consummation of a war in which religion served as a mask for ambition, brutality, and greed. The city most sacred to three faiths had become a graveyard, conquered in the name of Christ but stained with atrocities that betrayed his teachings.

Conclusion

The First Crusade began with the language of salvation and justice, but from its first steps it betrayed those ideals. Emperor Alexios I sought mercenaries to secure his throne, not an army of the faithful. Pope Urban II promised forgiveness through bloodshed, transforming violence into virtue and propaganda into gospel. The masses who responded—peasants, women, and children—marched not as disciplined defenders of the faith but as mobs whose first acts of “liberation” were the slaughter of their Jewish neighbors.

At every stage, the crusade revealed its true nature. Peter the Hermit led thousands to ruin in Asia Minor, their zeal ending in massacre. The conquest of Nicaea denied crusaders plunder while strengthening Alexios’s empire. Baldwin seized Edessa not as a crusader knight but as a usurper. At Antioch, famine and betrayal gave way to desecration, mass killing, and the manipulation of relics to sanctify despair. At Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān, desperation descended into barbarism, where men of the cross boiled flesh and roasted children. And in Jerusalem, the culmination of the crusade, supposed holy warriors drenched the city in the blood of Muslims, Jews, and Christians alike, desecrating the very place they claimed to liberate.

The First Crusade was not a “just war” by any measure. It was not limited in scope, nor restrained by mercy, nor guided by righteous intention. Instead, it was a war of ambition and survival, a campaign of plunder and power cloaked in the language of God’s will. Religion was the mask; greed, fear, and violence were the reality.

The crusaders may have won Jerusalem, but in doing so, they lost the moral foundation of the faith they claimed to defend. Their legacy was not the triumph of righteousness, but the enduring reminder of what happens when war is baptized as holy: atrocities are justified, hypocrisy reigns, and the cross itself is stained with the blood of innocents.