The Earliest Mentions of Muhammad from Syriac Sources

Long before medieval Christian polemicists wrote about “Mahomet,” and centuries before European historians tried to reconstruct early Islam, a different group recorded the rise of Muhammad and his followers in real time: Syriac-speaking Christians of the Near East.

These communities lived not in Rome or Constantinople, but in Syria, Mesopotamia, and Persia—the very lands conquered during Islam’s first expansion. They spoke Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, and belonged to ancient churches such as the Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church.

Because they stood closest to the events, they produced the oldest records of Muhammad, his followers, and the conquests that reshaped the Near East outside of the Quran. These accounts begin not generations later, but within a few years of Muhammad’s death and the expansion of the Arabs from the Hijaz. Their writings show us how Christian eyewitnesses first understood Islam—not as a world religion, but as a sudden Arab movement upending empires.

These sources are extracted from the book “Envisioning Islam: Syriac Christians and the Early Muslim World” by Michael Philip Penn, and show how Syriac writers described Muhammad within mere years of his death and how their understanding evolved as Islam took shape.

The Account of 637: Muhammad (637 CE)

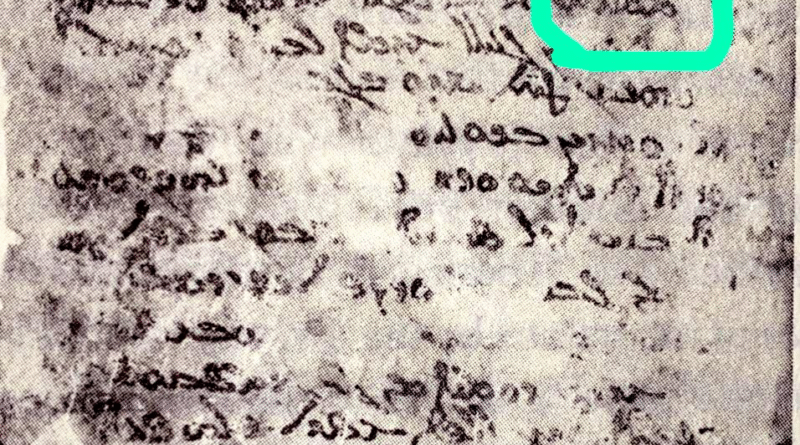

The single earliest surviving mention of the Islamic conquest appears not in a formal history, but scribbled in the blank space of a Gospel manuscript. The sixth-century codex British Library Add. 14,461, The Account of 637, contained Syriac translations of Matthew and Mark . In 637 CE, someone filled the first page with a hurried report on events unfolding around them:

. . . Muḥammad . . . [p]riest, Mār Elijah . . . and they came . . . and . . . and from . . . strong . . . month . . . and the Romans . . . And in January the . . . of Emessa received assurances for their lives. Many villages were destroyed through the killing by . . . Muḥammad and many were killed. And captives . . . from the Galilee to Bēt . . . And those Arabs camped by . . . And we saw . . . everywhe[re] . . . and the . . . that they . . . and . . . them. And on the tw[enty-si]xth of May, . . . went . . . from Emesa. And the Romans pursued them . . . And on the tenth . . . the Romans fled from Damascus . . . many, about ten thousand. And the follow- ing [ye]ar, the Romans came. On the twentieth of August in the year n[ine hundred and forty-]seven [i.e., 636 CE] there assembled in Gabitha . . . the Romans and many people . . . [R]omans were to[lled]about fifty thousand . . . In the year nine hundred and for[ty-eight]. (p.19-20)

Chronicle ad 640: The Arabs of Muhammad (640 CE)

Additionally, the Chronicle ad 640 spoke of battles between Byzantine forces and “the ṭayyāyē n Muhammad” (p. 106). For reference, the term ṭayyāyē was a common term used at that time to refer to Arabs.

The Khuzistan Chronicle (c. 660): Muḥammad as Leader of the Arabs

By the 660s, Syriac Christians had gained some distance from the shock of the conquests. The Khuzistan Chroniclewritten only ~30 years after Muhammad’s death, described the invaders as divinely sent:

“God brought against them the Sons of Ishmael [who were as numerous] as sand upon the sea shore. Their leader was Muḥammad. Neither walls nor gates nor armor nor shield withstood them and they took control of the entire Persian Empire. And Yazdgard sent countless troops against them and the ṭayyāyē destroyed all of them.” (p.21)

Here, Muhammad appears clearly as commander and catalyst for the Arab victories. The chronicler interprets the events through a theological lens—Islam’s rise as divine judgment, a common motif in late antique historiography.

The Chronicle ad 705: A Caliph List (705–715)

The Chronicle ad 705 was composed between 705 and 715, listing the rulers from Alexander the Great to the Umayyad Caliph Walid, who reigned in 705, and treating Muhammad simply as another political leader.

“[In] the year 932 of Alexander, the son of Philip the Macedonian [= 620/621 CE], Muḥammad entered the land. He reigned seven years. After him, Abū Bakr reigned: two years. After him, Umar reigned: twelve years. After him, Uthmān reigned: twelve years. After him . . .” (p. 35)

What made the sequence particularly striking was its detached presentation. Muhammad was just like any other king. No special acknowledgments or acknowledgments. One king followed the other, just as in any other kingdom. This text normalizes Muhammad and Islam’s rise: no divine significance, no apocalyptic panic—just political succession.

British Library Additional 14,643: Muhammad “Messenger of God”

One of the most startling finds comes from a mid-8th-century Syriac translation of an Arabic caliph list. This comes from the British Library Additional 14,643, which has been dated on paleographic grounds to the mid-eighth century. At its end appears a Syriac translation of an originally Arabic caliph list. The list finished with the reign of the caliph Yazid, suggesting that the Arabic version was written before Yazid’s death in 724 and was fairly soon afterward translated into Syriac. The list’s incipit initially read:

“A notice concerning the life of Muḥammad the messenger [rasulā] of God.” (p. 163)

A Christian scribe translated this phrase without objection—suggesting early Christians sometimes saw Islam as a form of non-Trinitarian Christianity, not a separate religion. However, later in history another hand violently erased the phrase: The original “Muḥammad … messenger of God” and altered the text to read “Muḥammad … is rejected.” (pp. 163–164). This indicates that the original Syriac Christians did not perceive Islam as entirely separate from their own tradition.

Conclusion

Taken together, these Syriac testimonies reveal a picture of Islam’s beginnings quite different from the neat theological boundaries later imagined by both traditions. Muhammad does not first appear in distant polemics or retrospective chronicles, but in the hurried margin of a Gospel book in 637, noted by a Christian who had just seen villages fall and armies flee. In the decades that follow, Syriac writers continue to mention him—sometimes as the commander of the Ishmaelites sent by God to topple empires, sometimes simply as the first king in a succession of Arab rulers, and occasionally, almost shockingly, as “the messenger of God,” before later hands physically scraped that phrase from the page.

In these earliest references, Muhammad emerges not as a mythic figure constructed by centuries of tradition, but as a real leader whose name carried weight in the living memory of Christians who survived the first wave of Islamic expansion. For a time, the boundaries between the two communities remained porous; some Christians could imagine Islamic monotheism as part of a broader, if heterodox, Christian landscape. Only gradually—through debate, polemic, and the pressures of empire and doctrine—did those borders harden, erasing earlier moments of ambiguity and coexistence.