“The Crown” Star Gives Us The Blueprint for Representation and Revolution

[ad_1]

Khalid Abdalla is a revolutionary. The Egyptian-British actor has lived many lives, from his footfalls in Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring to his masterful portrayals of some of the most complex Arab and Muslim characters that have graced our screens. Today’s streamers may know him as Dodi Al Fayed, the film producer and son of Harrod’s owner Mohamed Al Fayed, who was famously romantically linked with Princess Diana in the last days of her life and is depicted in the final two seasons of Netflix’s hit historical drama series, “The Crown.”

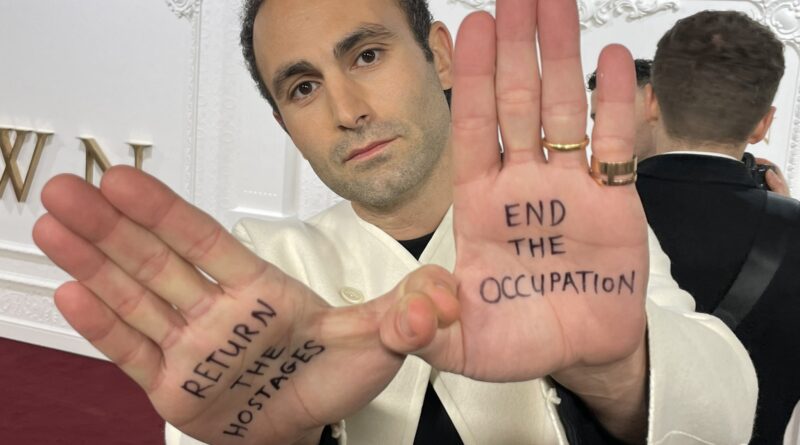

Abdalla’s many lives merged into one headline-grabbing gesture during the show’s red carpet premieres. In a bold statement that’s rarely seen in the world of TV and film, the starring actor aligned his activist identity with his acting career by using the photo op to stand in solidarity with Gaza. Abdalla was among the 4,400+ proactive artists and actors who signed the open letter demanding a Gaza ceasefire.

With the type of honesty that is usually confined to our Signal group chats, Abdalla sat down with Muslim Girl founder Amani for a deep dive into the personal philosophy and experiences that led him to this profound moment in our modern diversity era.

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

AMANI: There are so many different dots in your long and prolific career. What would you say is the connective tissue?

KHALID ABDALLA: I would say the connective tissue is a lot of the political issues that surround my Arab identity. That means, whether it’s as a person in this world, as an actor, or as a creative in various different parts of these industries, I am constantly asking myself the question of how best to be of service to the ideas that I believe in, in a world that is like the one around us — in which 20,000 people, at least, can be killed [in Gaza], and according to most of the world governments, that’s okay.

Those are questions that I have been facing, not just throughout my career, but throughout my life. I’m an actor who first started work and left university in 2003, the year of the war in Iraq. I started my career at the height of the Iraq war, and the war of terror. The power of that racist gaze upon me has been something that I have had to negotiate with throughout my working life.

But, of course, it’s something that goes much more deeply into my experience of being an Egyptian that is a third generation, in terms of my father and grandfather both being political prisoners of a long line of fighting for social justice and democracy and on the left of the Arab political spectrum.

I would ask myself the question, ‘Wait, how many Arabs can you think of in the history of cinema on this side of the world that you get to know, you get to love — not fear — and therefore when they die, you mourn them?’ I can barely think of any.

So, sometimes, as an actor, it’s taken me into certain films. As a person, it’s taken me to the barricades. The years of my engagement and fighting within the Egyptian revolutionary struggle, I see as connected to what I do as playing “Dodi Fayed,” or being in the “Kite Runner,” or even “United 93” way back when, or this conversation and my curiosity about how Muslim Girl started, right? This is a connected fight, as far as I’m concerned.

I don’t see myself as one body, I see myself as something connected to all of this. And I also think, unfortunately, these circumstances — I’m talking here as an Arab — often force us into multiple roles. We exist in a context in which our infrastructure is depleted, and I’m sure you feel this in Muslim Girl or in various things. You have to be multiple things. You are, by definition, having to be “plural.” Because the infrastructure doesn’t exist underneath you.

So, everyone’s like, “Wait, you do this and you do that? How?” My walking out onto that red carpet with “Ceasefire Now” is the most whole I have felt in my career. And I feel like it’s in some ways a long journey — it’s a long journey to be entirely in my body with my career in the past and hopefully the future. And, not just my career, but my family history.

It’s very hard for us, especially in the context of the gaze towards us that generally misunderstands us, to be able to hold a symbol that people will understand. Like, you know, you walk around with a headscarf. People are constantly misinterpreting that. I walk around as an Arab man.

People are constantly misinterpreting that, whatever it is, right? And, specifically in the context of playing Dodi, it hit me in my stomach in a really powerful way. I’ve played these roles and done what I do for some time now, and the thought had never even occurred to me that finally after 26 years, we got to mourn him.

There are big cultural questions around why this person, who also died on that day, is someone that people come up to me and ask, still, if he’s alive. It’s like his death was completely invisible, so I understand the value of telling his story on the scale of a platform like “The Crown” as a cultural intervention.

Our diaspora and stateless nature means we are also kind of organizationally orphans, right? We don’t have the resources of states behind us.

What I did not imagine and did not anticipate was how much it would resonate in the context of what’s happening now in Gaza. What I did not anticipate is that I would ask myself the question, “Wait, how many Arabs can you think of in the history of cinema on this side of the world that you get to know, you get to love — not fear — and therefore when they die, you mourn them?” I can barely think of any. There are some, but I can barely think of any. And, what does that in turn tell you about the cultural and political imaginary of the world we live in? You and I were brought up in it.

How much in turn does that affect people’s solidarity? You know, for you and me, we watch one of those videos and we see one of those kids say “mama” or “baba” and it destroys us. Because that’s what it means to us.

But — and this is what’s hard – understandably, that’s not the case for people who don’t have our experience. And that’s part of our work.

As far as I’m concerned, part of what I have been doing for the length and breadth of my career so far is working on that cultural imaginary while understanding that it’s not just about having a positive representation of people that look like us in media. Our diaspora and stateless nature means we are also kind of organizationally orphans, right? We don’t have the resources of states behind us.

In fact, those states are very often states that are putting us in prison. Like in my case, in Egypt with my friends, who are [political activists] in prison. And that’s the case across most of our region.

We’re political orphans in that sense and institutional orphans. So, yeah, that’s what joins the dots.

You’re using your platform to showcase how passionately you feel in our community about what’s happening right now. What immediately came on my radar was the very powerful statement that you were making on the red carpets for “The Crown.” Was there a distinct experience for you in making that kind of statement in Los Angeles, especially with all the censorship happening in Hollywood right now, and in London?

Here’s the funny thing: for me, and also in many ways, it actually started last year rather than this year, because at last year’s premiere, I did “#FreeAlaa” on my hand – and that was the first time I’d done that. I’m part of the campaign to free [Egyptian political prisoner] Alaa Abd El Fattah.

And, what’s interesting is I feel like we — and I’m speaking very, very broadly here as Arabs and Muslims — have been brought up to feel there are aspects of us that we have to hide in the public sphere because we’re going to be misunderstood, we’ll be attacked, we’ll be ostracized, whatever it is.

Actually, a lot of my career has shown that when you enter those spaces, you actually very often are welcomed in ways that you didn’t expect — and that’s amazing. That has been my experience all three times. That hasn’t made any of them any easier to do, but, actually, in all cases, I had conversations I didn’t expect to have. I’ve been welcomed by people that I didn’t even know what their opinions would be, and the kind of space around these things has expanded. However, at each turn, whether it was the premiere last year, the LA premiere, or the London premiere, I approached doing each of them with fear.

I did not know what the consequences would be. I had a long period of thinking, “Should I do this? Should I not do this? Is this the right thing? What is the right thing? What’s the right thing to write? How’s the right way to do it? Is it legitimate for me to do it? Is it not?” And conversations you have with your family, conversations you have with people who are close to you, who you agree with, and also Jewish friends and all sorts of things about prior to and around it, because it’s not just about the event itself. I think we all have cultural energies inside us that we discipline, and they stop us and prevent us from having conversations, sometimes even with ourselves.

I’m on a journey that I personally relate directly to 2011 and my time in Egypt, and where that goes in my family history. But, I’m also on a journey to expand my relationship with my own sense of freedom. The events of the past few months [in Palestine] have emboldened me to go, “If not now, when?” Like, I am in search of alignment.

A lot of my career has shown that when you enter those spaces, you actually very often are welcomed in ways that you didn’t expect — and that’s amazing.

I don’t say this just about Arabs or Muslims or whatever, I say this about most people. I think most people who live in this crisis-driven world are fundamentally out of alignment. And I’m searching for alignment.

Amongst some of the most inspiring stuff I’ve found over the last few months has been Jewish Voice for Peace and seeing American Jews take over Grand Central Station. I wept [while] seeing that, knowing how hard that must be for them. Like, as a gesture of solidarity, they recognize it’s not just about Palestinians in Gaza, but about their own futures as well. That’s amazing.Frankly, I drew as much encouragement from them as I did from what’s happening in Gaza.

I want to dig deeper into that thought process that you had when you were deciding to make a statement because a lot of our readers are young, and they struggle with this, especially in, for example, American society, where it is very much an extreme binary: you’re either with us or you’re against us, and people are very aware of the consequences of missing out on opportunities or jobs for speaking truth to power. So, when you are deciding to use this incredible opportunity that you have to make a statement, when you’re thinking like, “Should I do it or should I not,” what pushed you over the edge to be like, “No, I have to”?

The LA premiere was mid-November, so we’re talking six weeks from October 7. You know, I’ve wept every day. I was already headed that way.

But, actually, what pushed me over the edge was the alignment between Dodi and the resonance I was talking about earlier, in terms of the invisibility of Palestinian death. That was an alignment that I felt had to be honored. It goes to show where we are in the sense, that it’s not yet fully visible.

I didn’t have that thought for 20 years of my career. We’re used to the idea that the representation of us is bad. But, we don’t ask the question, “How many do you get to know and love? And, therefore, when they die, mourn them?”

On a deep personal level, that moment created a lived reality of what the world could be by then in its re-alliances of reformulating who people are on a cellular level, how their energy is spent, what they’re doing, who we can be.

So, I could not walk out onto that carpet as a whole person without making some statement that intervenes in the cultural landscape to go like, “No, I will not be seen as that silent version. I have to be seen as this version that thinks this right now and is willing to say it right now.” Otherwise, why am I here?

The red carpet is an important place to do it. The thing is, sadly, there aren’t many people with our background that get to walk on red carpets, which redoubles the fear as to what might happen to you if you say something. On the other side as well, I think there are a lot of people who have solidarity and are scared to declare it, not out of fear of declaring their solidarity, but just simply because they’re worried that they don’t have the grounding to be able to defend it — which intensifies the pressure on us.

I could not walk out onto that carpet as a whole person without making some statement that intervenes in the cultural landscape to go like, ‘No, I will not be seen as that silent version’ … Otherwise, why am I here?

Part of my journey is that I’ve been to Palestine three times. I first went to Palestine in 2000, and then in 2008, and then the last time was in 2014 or 2015. So, I’ve seen the collapse of Oslo, I was there just before the second intifada, I’ve seen the wall being built, and I’ve seen the wall complete. And, in 2000, I went to Gaza, so I also have the physical experience of being under occupation as an Arab body.

I’m not Palestinian, but I’ve grown up with Palestinians, and I’m an Arab on this side of the world and it’s all related. So, the journey for me to walk down that red carpet as Dodi in that particular moment is a long one. It’s, “How do I align all these experiences?” There was an opportunity for me, and I took it.

There is that anxiety of, “Oh, they let one of us onto a red carpet,” “They let one of us into a premiere,” or “Are they going to let us back in again?” It kind of feels like a pressure to be, like, the model minority in that moment.

Either that, or it’s just like you feel you’re disposable. You feel very disposable. I mean, that’s what you are as a minority. You’re in a situation where you’re encouraged to be palatable, and you fear that if you’re not, you’ll just be thrown away. It’s part of the game that people of our culture or our heritage have to play. [It’s] exactly as you say; it’s like, “Wait, is it more important that I hold onto my fame and my ability to be influential and open that space? Or, is it more important that I remain aligned and express?” They’re both different ways of being aligned. I’m not saying one is right and one is wrong. In my particular case, this is the place I’ve reached in my life.

I’m willing to take that risk, but I don’t feel like I’m taking that risk just for myself. As I say, I feel like it’s, hopefully, emboldening for others to feel that they can do the same. It’s like finding out, will doing so result in you being excised and never working again? Or, will it actually build new solidarities? Will it result in conversations that you wouldn’t have had otherwise, like this one? And where will that go?

I’m curious about your philosophy about the roles that you play because there is this very deep purpose in the work that you do. In “United 93,” for example, you portrayed a terrorist. You also starred in the “Kite Runner,” and related to a character like Amir. After I watched “The Crown,” I felt kind of uneasy about the way our people were represented because it kind of portrayed Dodi and his father as being so desperate for acceptance and integration within the British public to be seen as equals. In the context of the roles that you’ve chosen to play, how have you seen that evolution in terms of representation?

There’s a line between accepting to play and choosing to play. As in, what level they have to reach in general for them to be roles that are like, “I want to play this role.” In general, it’s about what comes to us and how we negotiate with that, and that’s a choice — absolutely. But, the fabric of what you’re doing relates to the world around you as it is at that time.

I’m very proud of all the roles I’ve played. I think “The Crown” deals with it quite personally and sensitively. This is one of our problems: it’s because the representations of us are few and far between in big films and media and all of those kinds of things, there ends up being a huge amount of pressure on any representation to carry other responsibilities that may not be its own.

I’m willing to take that risk, but I don’t feel like I’m taking that risk just for myself … I feel like it’s hopefully emboldening for others to feel that they can do the same.

So, if a film is made about Palestine or Iraq or whatever it might be, we always want it to say everything; we’re always like, “They didn’t do this,” and, “This is what’s wrong with it.” In relation to Dodi and Mohamed Al Fayed’s story, there is this slight conflict between being true to what happened and an awareness that there are representational responsibilities — because there are very few of these kinds of representations in cinema — and how do you triangulate between those two?

There’s a phrase that I like very much, which is, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” One of the reasons it rhymes is that, structurally, things end up being similar, and until you can move things structurally, it will feel the same.

One of the phrases from the Palestine Festival of Literature that I like very much is taken from Edward Said, which is, “The power of culture over the culture of power.” Unfortunately, that phrase is resonant because the culture of power is way more dominant in our region, whether it’s from our governments or governments that occupy and fight wars against us.

So, your approach would be to dedicate less energy to be included and focus on our own stories in our own current context?

There’s no single answer. We need all of those answers to work as strongly as possible for us in the various contexts that we find ourselves in.

Someone who is an actor who’s doing their first role is going to answer that question differently to someone who is originating their own project and is a writer and is able to be in rooms where they can get projects greenlit. And we need all of those answers working as hard for us as possible, while at the same time I think knowing that compromising and negotiating can be useful.

However, I don’t think pandering ever is, because I think there can be pressure on us to shut ourselves down. That’s never useful.

So long as what you’re doing is pushing things forward, whether it’s by a millimeter or ten miles, I think is worth doing.

That’s how I interpreted your statement on the red carpet. It’s like, “Okay, you want me to be here; I’m not just going to be a smiling face.”

This is what diversity looks like.

You have such a tremendous career in acting. Was it that as you ascended in your acting career, you found the means to become more vocal about issues that you’re passionate about? Or, is it that you’re an activist and you’ve broken into these different spaces to become more influential for the purpose of the issues that you advocate for?

I’ve tried to keep them parallel throughout my life. I used to think of them at war with each other. I used to think these different parts of me were in conflict: the actor, the director, the writer, and the activist. I had a moment where I shifted and I was like, “No, they have a harmonic relationship with each other.” I started to think of them more as like a symphony or a quartet.

They build on each other and you never quite know which identity is the one that actually allows this one to solo best at this moment. That was like a major cellular shift inside my body.

I think there can be pressure on us to shut ourselves down. That’s never useful.

The actor side of me is very important to me, but it’s not my only identity. It might at this moment be the most front-facing. When I was in Egypt in 2011, the activist and organizing part of me was much more front-facing, and that meant that I was also doing a lot of journalist-type work, a lot of media interviews, all sorts of things in service of the world I think we need in order to get out of this hellhole.

I think our role as a generation is to expand the boundaries of solidarity and to create and expand the cultural space around difficult conversations to do with our identity while doing that with warmth. Creating safe spaces for that to happen is really important.

I think we can fall into this pitfall, even though I think it also has its value of being shrill. And, you can’t have a difficult conversation unless you feel safe to do so; you’ll just shut down otherwise.

So, even from a media perspective, how do we do that? I think that’s part of our challenge. I think there is a hell of a lot more solidarity out there for us than is able to be expressed, so how do we expand the space in which it can begin to be expressed? That’s been one of the huge joys and pleasures of what I’ve done so far in terms of my experience.

What is your hope for the work that you’re doing in contribution to the collective and the bigger picture?

My big hope is to dream that big that we are the generation in which this ends, in which that shift in global consciousness truly happens.

When I was born, the West Bank had been occupied for 13 years. Now, my children are six and seven. I cannot accept that my children, in another 30 years, are in the same position I’m in now.

My big hope is to dream that big that we are the generation in which this ends, in which that shift in global consciousness truly happens.

I want to put myself in service, not just in relation to Israel-Palestine and all of that kind of thing, but in relation to the broader issues around the politics that destroy our region. I want to put myself in service of that, both in terms of the work that I do in film and the arts generally, and as a creative, but also on the ground, political work, whatever it might be. I want to put myself in service of that trajectory.

I see my role within that as predominantly cultural work. In order for something to happen, we have to be able to imagine it. And that’s the sort of difficult intellectual, cultural work that we do in terms of manifesting it, representing it, and finding ways in which to express it, which creates all sorts of alliances.

That’s my primary work now, and I would hope for the rest of my career – but it’s not my only work. I hope over time to build a production company and to play my role in making happen the work that allows those stories to be told more and more. I’m trying to do that work as an actor, as a writer, as a director, as a producer, as the range of identities to build those alliances, for us to find each other. I want to do that while staying true to the fundamental idea that my own personal star rising is meaningless in the context of my people being killed or being put in prison. It’s meaningless.

It has to be aligned with those struggles. It doesn’t have to achieve those goals, those ends, but it has to be aligned with those struggles. I don’t want to be famous in order to be famous for Khalid Abdalla.

It’s like, what’s the point of protecting that fame or that privilege if you’re not putting it to use for liberation?

When thousands of people are being killed and you’re at the same time being asked to represent them on screen, any form of representational politics around our bodies is broken, from democracies to films and media.

To do the work of creating those realignments is our job in this generation. And that means taking risks. It really means taking risks. There’s no other way, but they have to be meaningful risks.

Follow Muslim Girl across all social media platforms for more groundbreaking conversations.

[ad_2]