The Creation of the Trinity

[ad_1]

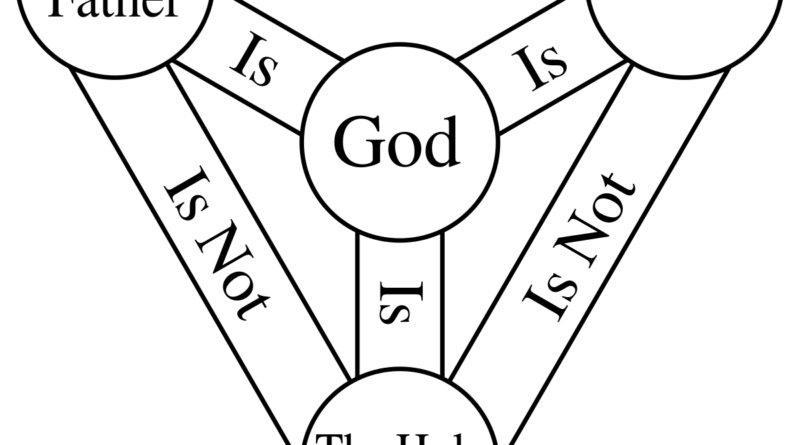

The doctrine of the Trinity is a central tenet of Christian theology, articulating the understanding of God as one being in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The major points that make up the doctrine of the Trinity are as follows:

- There is one God

- God is a trinity of persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

- Each person is distinct from the other.

- Each person is fully God.

- The persons consist of one substance.

- Each person is eternal and uncreated.

- Each person is equal to the others.

- Each person is equally powerful.

- God does not exist without any one of the three persons.

Trinitarians believe that for a person to be considered a true Christian, they must accept all the above points. Otherwise, they are to be considered heretics and not part of the fold of Christianity. Ironically, this would mean that all Christians before the fourth century were heretics, as this doctrine was not formulated and codified until this time period.

FORMULATION OF THE TRINITY

This Trinity, as it is understood today, was the outcome of a series of ecumenical councils, starting with The First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. These councils addressed various theological disputes, including the nature of Christ and his relationship to God the Father and the Holy Spirit. Here are the key councils that took place before the doctrine of the Trinity was fully articulated and affirmed:

- First Council of Nicaea (325 CE): This council was convened by Emperor Constantine to address the Arian controversy, which questioned the divinity of Jesus Christ. The council affirmed the full divinity of the Son, declaring Him to be “of the same substance” (homoousios) with the Father. The Nicene Creed, formulated here, laid the foundational language for the Trinity, emphasizing the unity of the Father and the Son. It is worth noting that the Holy Spirit was not officially part of the Trinity.

- First Council of Constantinople (381 CE): This council expanded the Nicene Creed to include a more detailed description of the Holy Spirit, affirming His divinity and procession from the Father. It declared the Holy Spirit to be worshipped and glorified with the Father and the Son, further solidifying the concept of the Trinity.

- Council of Ephesus (431 CE): While the main focus of this council was to address the Nestorian controversy over the nature of Christ and affirm the title of Theotokos (God-bearer) for Mary, it also contributed to the understanding of the unity and distinction within the Trinity through its Christological declarations.

- Council of Chalcedon (451 CE): This council further clarified the nature of Christ as being fully divine and fully human in one person. Though its primary focus was Christological, by defining the two natures of Christ, it indirectly contributed to the Trinitarian understanding by emphasizing the relationship of the divine and human within Christ, thus presupposing a clear Trinitarian framework.

Through their creeds and declarations, these councils gradually articulated the doctrine of the Trinity. They addressed the nature of God as one essence in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, co-equal and co-eternal. The debates and decisions of these councils reflect that the Christianity practiced today by most Christians is a form of Christianity that was created hundreds of years after the death of Jesus.

Not only did the doctrine of the Trinity not exist until the fourth century, but all evidence points to the fact that no Christian understood the Trinity as it is established today before these ecumenical councils. The proof is that there was no Trinitarian faction before this period, but numerous competing ideologies.

COMPETING DOCTRINES

In the centuries following Jesus’ death and before the formalization of the doctrine of the Trinity, there were a number of competing doctrines and theological interpretations within early Christianity. Most notably, groups of Jewish Christians who recognized Jesus as a human Messiah, like the Ebionites, Nazoreans, and Elkesaites, and others who recognized Jesus as divine but rejected the Trinity as it is understood today. Some of the competing ideologies that viewed Jesus as more than a human messiah were the following below, with the more noteworthy ideologies in blue:

Arianism:

Jesus is not co-eternal, Not Co-Equal with God

This doctrine, proposed by Arius, a priest from Alexandria, denied the full divinity of Jesus Christ. Arius argued that Jesus, while unique and divine, was created by God and thus not co-eternal or co-equal with God the Father. Arianism was a major force in the early church and was one of the main issues addressed at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE.

- John 14:28: “You heard me say, ‘I am going away and I am coming back to you.’ If you loved me, you would be glad that I am going to the Father, for the Father is greater than I.”

- Arians interpreted this to mean that Jesus, as the Son, is subordinate to the Father, thus not co-eternal or co-equal.

Modalism or Sabellianism:

no distinction between 3

This doctrine asserted that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not distinct persons but different modes or aspects of one God. According to Modalism, God manifested Himself in different forms at different times.

- John 10:30: “I and the Father are one.”

- John 14:8 Philip said to him, “Lord, show us the Father, and we shall be satisfied.” 9 Jesus said to him, “Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father; how can you say, ‘Show us the Father’? 10 Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father in me? The words that I say to you I do not speak on my own authority; but the Father who dwells in me does his works. 11 Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father in me; or else believe me for the sake of the works themselves.

- Modalists interpreted such verses to mean that God is a single person who manifests in different forms rather than three distinct persons.

Adoptionism:

Jesus was created mortal, but became divine

This belief proposed that Jesus was born as a mere man and was adopted as the Son of God at some point in his life (often believed to be at his baptism or resurection). Adoptionism suggested that Jesus’ divine status was granted to him due to his righteousness and obedience.

- Mark 1:11: “And a voice came from heaven: ‘You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.’”

- Romans 1:3 the gospel concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh 4 and designated Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord,

- This could be interpreted as Jesus being designated as God’s Son at his baptism.

Subordinationism:

God is above Jesus and Holy Spirit

Origen of Alexandria (c. 184 – c. 253 CE) was an early Christian scholar, theologian, and one of the most influential figures in early Christian theology. Origen is often associated with a form of subordinationism, a belief that within the Trinity, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are subordinate to the Father in nature and being. He viewed the Father as the supreme source and the Son as eternally generated by the Father. The Holy Spirit was also seen as subordinate to the Father and the Son. Additionally, Tertullian (c. 155–c. 240 CE) also saw the Son and the Spirit as distinct from the Father in rank and glory, though he affirmed their unity in substance.

Docetism:

Jesus is purely divine – no physical body

This belief held that Jesus only appeared to be human but was purely divine. According to Docetism, Jesus’ physical body and his sufferings were mere illusions. This view was generally associated with Gnostic groups who viewed the material world as evil.

- John 1:1-14: The opening verses describe the Word becoming flesh. Docetists would focus on the divine aspect (“the Word was God”) to the exclusion of the incarnation.

- This doctrine was more influenced by Gnostic thinking than by specific biblical texts.

- See Divine Hypostasis

Nestorianism:

Jesus had two persons, one human and one divine

Proposed by Nestorius, this doctrine suggested a clear distinction between the divine and human natures of Christ, almost implying two separate persons in Jesus. This view was condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE.

- John 2:4: Jesus addresses his mother Mary as “Woman,” which Nestorians used to argue for a distinction between Jesus’ divine and human aspects.

- Matthew 26:39: In Gethsemane, Jesus prays, “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will. ” This indicates a distinction in wills.

Monophysitism:

Jesus is one person who is fully human and fully divine

In contrast to Nestorianism, Monophysitism held that in Jesus Christ there was only a single divine nature, rather than two natures (divine and human). This doctrine was prominent in Eastern Christianity but was rejected by the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE.

- John 1:14: “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” Monophysitists emphasized the unity of Christ’s nature as essentially divine.

- Philippians 2:6-7: Jesus, “being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness.”

Apollinarianism:

Jesus human body with a divine spirit (not fully human)

Proposed by Apollinaris of Laodicea, this doctrine taught that Jesus had a human body but a divine mind and spirit. It essentially denied the full humanity of Jesus.

- John 1:14: “The Word became flesh.” Apollinaris might focus on the divine Logos indwelling the human flesh.

- Philippians 2:7: “but emptied Himself, taking the form of a bond-servant, and being made in the likeness of men.”

DID THE TRINITY EXIST BEFORE THE FOURTH CENTURY

While it can be argued that fragments of the Trinity doctrine as it is understood today existed before the fourth century, there is no indication that any Christian prior to this believed all the premises in a single established doctrine. This means that Christianity, as it is understood today, is a new innovation, not what was originally preached by Jesus or his closest followers. Therefore, this would imply that all Christians before the Trinity were heretics.

The following article and corresponding presentation goes over each of the supposed quotes that Trinitarians utilize to attempt to claim that the Trinity existed before 325 CE.

While I wold love to repaste the entire article here, I think that may be a bit excessive. Instead, I would like to pull from the author’s conclusion, which summarizes his findings regarding the claim that the Trinity existed before the fourth century.

After analyzing Slick’s six alleged trinitarian authors before Nicea, we are left utterly empty-handed. Polycarp did not believe in the Trinity nor did Justin, Ignatius, Irenaeus, Tertullian, or Origen. Now, of course, this doesn’t mean that no one believed in the Trinity before Nicea, but it shows that something is deeply flawed in Slick’s methodology. Perhaps an analogy will help to explain the fallacy here. If someone in 2019 says, “I love using Instagram,” we know that such a person is referring to the social media app that takes pictures, applies filters, and shares those images with their network of followers. However, if a lady in 2005 says, “I love using Instagram,” we would be right to question her statement, since the app we know as Instagram didn’t exist until 2010. Perhaps she referred to an instant way to cook chickpeas, which are also called grams. Maybe she married and instantly got a grandmother as a result—an insta-gram. Or, maybe there’s some other explanation, but we know that whatever a 2005 person means by “Instagram,” it could not possibly refer to the social media network. But, what if someone had a theory that Instagram really did exist in 2005 and wanted to go about proving this? How would he go about it? He could find quotes from people that year talking about taking digital pictures, applying filters, and instantly sending them to friends. However, we had all those capabilities in digital cameras, Photoshop, and instant messaging services since the 1990s. This wouldn’t be enough to prove that Instagram existed in 2005. Furthermore, he could even find quotes about people uploading their images to social media, but that still wouldn’t prove anything since both Myspace and Facebook already existed then and people readily shared images on them. No, we would need evidence that these components (taking photos, adding filters, and sending them) were done as part of the Instagram service. Perhaps there was an early beta test of Instagram five years before the real version came out? It would be a tough, but not impossible case to prove, and the burden of proof would be on the person positing the existence of Instagram before 2010.

So it is with the Trinity. We know this idea did not emerge fully formed until the fourth century, and it wasn’t codified until the Creed of Constantinople in 381. We need someone to show that Christians were not just using various components of the Trinity theory, but that they understood them to relate to each other in a trinitarian way. Otherwise, we are left with a late Trinity. It will not do to merely assert along with Slick that, “the Trinity is a biblical doctrine, and it was taught before the council of Nicea in 325.”[19] It won’t do to quote a smattering of church fathers who made statements compatible with later Trinitarianism. It won’t do to even find people using the word “Trinity” in their writings. We need to see the whole set of beliefs that comprise a minimal understanding of the Trinity. In all the cases above, not only did we fail to see a single example of that, but we also saw that each author made statements incompatible with any Trinity theory. We simply cannot presuppose the Trinity and then read it into second and third century authors.

Now, some apologists have tried to argue the much more basic point that the ante-Nicene fathers believed Jesus was God, listing out a catena of proof texts to that effect. However, we know all kinds of theories included this belief from Arianism to Modalism to the Gnostics. No, we need to see an author calling Jesus God in a trinitarian way. They need to mean Jesus is God in that he is equal to the Father and the Spirit, eternal like the Father and the Spirit, consubstantial with the Father and the Spirit, and not merely a part or portion of God. Furthermore, the ancient world had several more categories of deity than are prevalent today. For example, the Hebrew mindset had no problem applying the word God in a secondary sense to Moses (Exodus 7.1), angels (Psalm 8.5; cf. Hebrews 2.7), the divine council (Psalm 82.1, 6), Israel’s judges (Exodus 21.6, 22.8), the Davidic king (Psalm 45.6), the belly (Philippians 3.19), those who receive the word of God (John 10.34-35), and even Satan (2 Corinthians 4.4).[20] Furthermore, in the Greco-Roman world, they called a wide range of beings Gods, including the pantheon of high Gods, regional Gods, deceased emperors, and a whole host of other lower-level divinities. In other words, God was a flexible word during the early centuries of Christianity and we need to take that into account when trying to prove this or that about patristic authors.

One last methodological issue I want to address, before moving on to discuss Nicea briefly, is the tendency among church historians to assume the inevitability of a fourth-century Trinitarianism. Instead of telling us what this or that person believed in his own time, we get vague statements about how someone was trying to articulate the Trinity, but just didn’t have the language or philosophy or intellect to quite get there yet. This is not a helpful way of doing history. Now, it’s fine to measure someone based on what became a later dominant theory, but we should not presume that he was trying to articulate that later idea and just fell short. For example, Tertullian did not believe in the Trinity. He had a trinity theory, but it contradicted the coequality of the later versions, since it featured the Father as the sole supreme God who had more divine substance than the Son. So, it’s dishonest for us to label Tertullian a trinitarian. Besides, no one is pressuring us to agree with what any particular author says. It’s not like the bible, where the text carries God’s inspiration and authority. No, church fathers contradict each other all the time, and that is totally normal. Think about Christian books written today. Do they ever contradict each other? Of course they do, because authors are fallible people who are trying to figure out this or that aspect of theology. So, rather than squeezing everyone into our predetermined mold, let’s allow each to speak on his own, whether he is orthodox or not.

Although it would be quite a task, the best scenario would be for a team of fair-minded researchers to wade through, systematically and objectively, all the Christian literature prior to 381 to locate and categorize all the relevant triadic, Christological, and pneumatological statements. Then we can see who believed what and discern the overall trajectory of theology in the period. But, even if this task looms in the future for those willing to take up the charge, we can still depend on previous investigations like that of Alvan Lamson. His words, though encased in the stolid style of nineteenth century literary sensibilities, reveal earth-shattering truths that bear directly on our inquiry.

After what has been said in the foregoing [395] pages, we are prepared to re-assert, in conclusion, that the modern doctrine of the Trinity is not found in any document or relic belonging to the Church of the first three centuries. Letters, art, usage, theology, worship, creed, hymn, chant, doxology, ascription, commemorative rite, and festive observance, so far as any remains or any record of them are preserved, coming down from early times, are, as regards this doctrine, an absolute blank. They testify, so far as they testify at all, to the supremacy of the Father, the only true God; and to the inferior and derived nature of the Son. There is nowhere among these remains a co-equal Trinity. The cross is there; Christ is there as the Good Shepherd, the Father’s hand placing a crown, or victor’s wreath, on his head; but no undivided Three,—co-equal, infinite, self-existent, and eternal. This was a conception to which the age had not arrived. It was of later origin.”[21]

Now, I’m willing to dismiss Lamson’s findings, if someone brings out evidence to the contrary, but until that happens, his conclusion stands.

[4:171] O people of the scripture, do not transgress the limits of your religion, and do not say about GOD except the truth. The Messiah, Jesus, the son of Mary, was a messenger of GOD, and His word that He had sent to Mary, and a revelation from Him. Therefore, you shall believe in GOD and His messengers. You shall not say, “Trinity.” You shall refrain from this for your own good. GOD is only one god. Be He glorified; He is much too glorious to have a son. To Him belongs everything in the heavens and everything on earth. GOD suffices as Lord and Master.

يَـٰٓأَهْلَ ٱلْكِتَـٰبِ لَا تَغْلُوا۟ فِى دِينِكُمْ وَلَا تَقُولُوا۟ عَلَى ٱللَّهِ إِلَّا ٱلْحَقَّ إِنَّمَا ٱلْمَسِيحُ عِيسَى ٱبْنُ مَرْيَمَ رَسُولُ ٱللَّهِ وَكَلِمَتُهُۥٓ أَلْقَىٰهَآ إِلَىٰ مَرْيَمَ وَرُوحٌ مِّنْهُ فَـَٔامِنُوا۟ بِٱللَّهِ وَرُسُلِهِۦ وَلَا تَقُولُوا۟ ثَلَـٰثَةٌ ٱنتَهُوا۟ خَيْرًا لَّكُمْ إِنَّمَا ٱللَّهُ إِلَـٰهٌ وَٰحِدٌ سُبْحَـٰنَهُۥٓ أَن يَكُونَ لَهُۥ وَلَدٌ لَّهُۥ مَا فِى ٱلسَّمَـٰوَٰتِ وَمَا فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ وَكَفَىٰ بِٱللَّهِ وَكِيلًا

[5:73] Pagans indeed are those who say that GOD is a third in a trinity. There is no god except the one god. Unless they refrain from saying this, those who disbelieve among them will incur a painful retribution.

لَّقَدْ كَفَرَ ٱلَّذِينَ قَالُوٓا۟ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ ثَالِثُ ثَلَـٰثَةٍ وَمَا مِنْ إِلَـٰهٍ إِلَّآ إِلَـٰهٌ وَٰحِدٌ وَإِن لَّمْ يَنتَهُوا۟ عَمَّا يَقُولُونَ لَيَمَسَّنَّ ٱلَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا۟ مِنْهُمْ عَذَابٌ أَلِيمٌ

[112:0] In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful

[112:1] Proclaim, “He is the One and only GOD.

[112:2] “The Absolute GOD.

[112:3] “Never did He beget. Nor was He begotten.

[112:4] “None equals Him.”

(٠) بِسْمِ ٱللَّهِ ٱلرَّحْمَـٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ

(١) قُلْ هُوَ ٱللَّهُ أَحَدٌ

(٢) ٱللَّهُ ٱلصَّمَدُ

(٣) لَمْ يَلِدْ وَلَمْ يُولَدْ

(٤) وَلَمْ يَكُن لَّهُۥ كُفُوًا أَحَدٌۢ

[ad_2]