Iran amid conflicting geopolitical dynamics in the Middle East

[ad_1]

A new Middle East is emerging as two contradictory trends of de-escalation in the Persian Gulf and a new round of war between Palestinians and Israelis are unfolding at the same time. This transformation comes after a period of extensive U.S. military involvement in the region, the unsuccessful civil uprisings of the Arab Spring, the emergence and decline of ISIS, and a number of tense proxy conflicts. While regional actors have taken steps to ease tensions in recent years — Saudi Arabia has prioritized economic development based on its Vision 2030 plan, Turkey has recalibrated its bilateral relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, the Qatar blockade has ended with the January 2021 al-Ula declaration, Israel has made strides toward regional integration through the Abraham Accords and normalization talks with Saudi Arabia, and Tehran and Riyadh have resumed diplomatic ties after a seven-year hiatus — the Oct. 7 attacks serve as a reminder that the region will not move past security concerns until the Palestine-Israel conflict is addressed. Meanwhile, Iran is trying to play its best cards and navigate its position vis-à-vis both regional de-escalation and the new conflicts unfolding in the Middle East.

Iran and de-escalation in the midst of regional crises

Iran views the current de-escalatory trend in the Persian Gulf as the outcome of its security achievements over the last decade. Tehran believes that its defined regional role is finally being established and legitimized, providing fertile ground for regional reconciliation. As the Iranian authorities see it, regional developments following the Arab uprisings have positioned Iran as a dominant geopolitical actor in the Middle East. As a result, they attribute the increasing inclination of Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries to improve ties with Iran to their acceptance of it as an indispensable regional actor. Speaking on a television program earlier this year, Mohammad Jamshidi, President Ebrahim Raisi’s deputy chief of staff for political affairs, emphasized Iran’s achievements in the Middle East over the last decade and reiterated that the current de-escalation mode among key regional actors and the inclination toward integration are rooted in Iran’s successful regional policy and its emphasis on a “resistance” attitude.

Since the 1979 revolution Iran has perceived itself as a key regional actor that had been left out of the U.S.-centric Middle Eastern order. Feeling threatened by the U.S. and its allies in the region, Iran has adopted a defensive approach and based its security doctrine on warding off threats to its territorial integrity and the survival of its political system. The Arab Spring uprisings and the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 created an opportunity for regional powers to have greater flexibility and maneuverability. Iran took advantage of this to adopt a more offensive approach with an eye to expanding its reach and power in the region. As Tehran sees it, its efforts have paid off, enabling it to accomplish most of its defined security objectives. Consequently, it has transitioned from a revisionist to a status quo power.

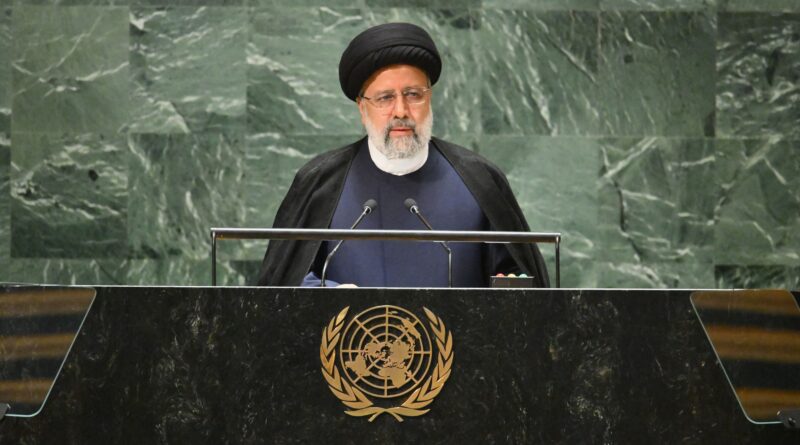

The question that arises next is how Iran envisions the future of the region following de-escalation and how it sees bilateral relations with its regional rivals evolving going forward, especially Saudi Arabia. The answer can be found by reading between the lines of President Raisi’s September speech at the U.N. General Assembly. In short, Iran sees security stabilization and economic development throughout the region as intertwined. In Raisi’s words, the stabilization of security in the Middle East depends on meaningful economic cooperation between regional actors and collective development. Well aware of the fact that Saudi Arabia is strengthening its security independence and diversifying its foreign policy options, Iran is not willing to just pave the way for Riyadh to advance its development agenda. If Iran perceives that its rival is benefiting more from this new trend of de-escalation, it might choose to reverse it.

The current war in the Middle East has also helped to give Iran more options. Consequently, expanding economic, diplomatic, and political ties at both the bilateral and multilateral levels can help maintain the possibility of achieving peace and stability. While changing long-standing patterns of friendship and enmity is not easy, regional de-securitization is a prerequisite for continued de-escalation in the Persian Gulf. External powers such as the United States, the European Union, and China can play a constructive role in stabilizing the region. Reviving negotiations on Iran’s nuclear program and holding an Iran-GCC summit are initial measures that would help to stabilize the regional de-escalation process. As a strategic partner of most of the Persian Gulf countries, China can play an active role in expanding multilateral ties between Iran and the Arab states of the Gulf.

The Gaza war and Iran’s cards

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has publicly announced that Iran was not involved in the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks on Israel and Iranian policymakers have called for an urgent ceasefire in Gaza. However, the Gaza war has provided Iran with ample opportunity to safeguard its regional achievements and pursue new objectives. Firstly, the war has validated Iran’s belief that the normalization of relations between Arab states and Israel does not result in regional security and stability but rather leads to instability and chaos. Secondly, these attacks have posed numerous internal challenges for the Netanyahu government, making it difficult for it to remain in power. Thirdly, despite Iran’s strong denial of involvement in the conflict, its pivotal role in the “Axis of Resistance” has demonstrated its indispensability to external powers, including the United States. This chaotic situation has shown regional and global powers that it is not feasible to redefine the regional order without including Iran.

For now, the future of the Gaza war is unclear. According to Reuters, in a meeting with Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in early November, Ayatollah Khamenei said Iran would not directly intervene in the conflict on Hamas’ behalf, as Iran did not receive prior warning about the Oct. 7 attacks. However, Khamenei emphasized Iran’s unwavering political and moral support for Hamas and reiterated that Iran would only intervene if it were directly attacked by Israel or the United States. Despite this stance, the conflict has provided Iran with a number of significant bargaining chips. Considering its influence over the Axis of Resistance network, Iran plays a key role in expanding or limiting the scope of the war. It can act as an informal mediator to facilitate a ceasefire or prisoner swaps, as it did with the release of 23 Thai hostages in late November, when it mediated between Hamas and Thai officials. Moreover, citizens of Arab countries view the situation in Gaza differently from their ruling elites. This gap also exacerbates the challenges for Persian Gulf states to adhere to the Abraham Accords and its anti-Iran counterbalancing function.

Iran, which has been an outcast in the U.S.-led regional order since the 1979 revolution, has adapted to pursue its security interests amid chaos and regional crises. While Tehran supports the establishment of an indigenous regional security mechanism, it recognizes that the U.S. will not completely withdraw from the Middle East in the near future and is mindful that the Gulf countries also seek to expand their security ties with Washington. As a result, Iran views the region’s geopolitical and security conflicts as a chance to uphold its position and leverage it to advance its defined national interests.

Zakiyeh Yazdanshenas is a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Middle East Strategic Studies in Tehran. Twitter: @YzdZakiyeh.

Photo by ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.

[ad_2]