Did the Story of Samson and Delilah Originate from Ancient Mythic Roots?

Few biblical tales are as vivid and dramatic as that of Samson and Delilah. Found in Judges 13–16, it tells of a man of unmatched strength who is betrayed by the woman he loves. For many, it is a moral warning against temptation and misplaced trust. Yet the story’s imagery, structure, and language suggest something deeper — an echo of an ancient, universal myth: the eternal dance between the Sun and the Night.

Read through a mythic lens, Samson is not only a judge of Israel but a solar hero — radiant, powerful, and destined for a blazing end. Delilah, in turn, becomes more than a treacherous lover; she is the personification of encroaching night, steadily dimming the sun’s rays until darkness reigns. This interpretation connects the biblical account to a web of Near Eastern and Mediterranean mythologies that long predate the written book of Judges.

Summary of the Story of Samson (Judges 13-16)

The story of Samson, told in Judges 13–16, begins during a time when Israel is under Philistine oppression. An angel appears to the barren wife of Manoah, announcing she will bear a son dedicated to God from birth as a Nazirite, bound never to cut his hair, drink alcohol, or touch anything unclean. This child, Samson, is destined to begin delivering Israel from the Philistines.

As a young man blessed with supernatural strength from God’s Spirit, Samson desires a Philistine woman from Timnah, and on the way to arrange their marriage, he kills a lion with his bare hands. Later, finding bees and honey in its carcass, he turns the incident into a riddle at his wedding feast. When the Philistines solve it by pressuring his bride, Samson kills thirty men in Ashkelon to settle the wager. After his wife is given to another man, he burns Philistine crops by tying torches to foxes’ tails, prompting retaliation that results in her and her father’s deaths.

In revenge, Samson slaughters many Philistines, escapes captivity by breaking his bonds, and kills a thousand men with a donkey’s jawbone. Later, in Gaza, he tears the city gates from their hinges and carries them away. He then falls in love with Delilah, who is bribed by Philistine leaders to learn the secret of his strength.

After repeated questioning, Samson reveals it lies in his uncut hair. While he sleeps, she has it cut, and the Lord’s strength departs from him. Captured, blinded, and imprisoned, Samson is brought out during a Philistine temple festival to be mocked. With his hair growing back, he prays for one final burst of strength, pushes down the temple’s two central pillars, and kills himself along with thousands of Philistines — more in his death than in his life.

Samson’s Solar Identity

Samson's Hebrew Name, Shimshon shemesh (שֶׁמֶשׁ), meaning “sun.” This is no minor coincidence. In ancient Israel’s cultural neighborhood, the sun was often deified — Shamash in Mesopotamia, Shapash in Canaan — associated with strength, justice, and divine oversight. Naming a hero after the sun instantly places him in a long tradition of solar champions.

Samson’s uncut hair is more than a ritual sign of his Nazirite vow; it’s a physical embodiment of solar rays. Just as the sun’s brilliance radiates outward, so Samson’s hair signifies his divine vitality. When Delilah cuts it, she is not merely breaking a vow — she is shearing the sun’s light from the sky.

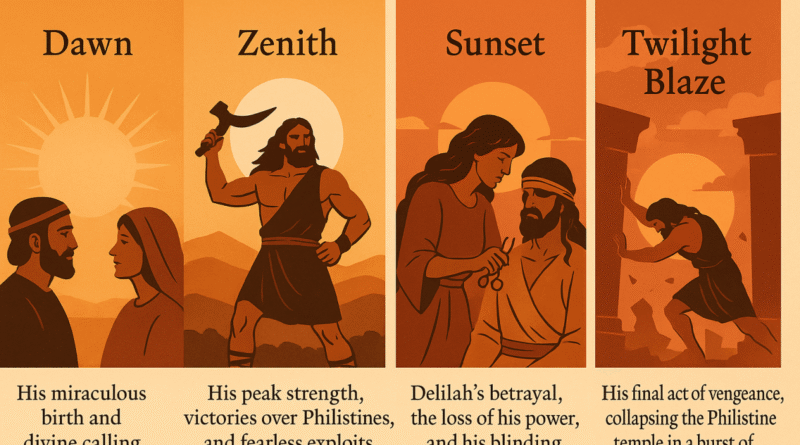

Samson’s life unfolds like a day in the life of the sun. At dawn, his story begins with a miraculous birth and a divine calling that sets him apart from the start. He reaches his zenith in the full blaze of his strength, achieving great victories over the Philistines and performing fearless exploits. As the sunset approaches, Delilah’s betrayal strips him of his power, leading to his capture and blinding.

Samson’s final act — pushing down the two pillars of the Philistine temple — can be read as the sun’s last blaze before disappearing over the horizon. The two pillars could symbolize the twin supports of the sky or the cosmic gates through which the sun passes at dawn and dusk in ancient cosmology. In that one last act, the sun-hero fulfills his destiny: overwhelming his enemies in a flash of destructive glory before yielding to the night.

Delilah as the Night

Delilah’s name (DĕlilāhDella) May Derive from the root dalal (דָּלַל) — “to weaken, bring low.” Phonetically, it also resonates with laylah (לַיְלָה), “night.” Whether intentional or not, the connection is compelling: Delilah is the one who weakens the sun until its light fades into darkness.

Delilah’s persistence mirrors the way night approaches — not in one sudden strike, but gradually, inevitably. She presses Samson repeatedly for his secret, just as twilight slowly overtakes daylight. When she finally cuts his hair, she symbolically clips the sun’s rays, plunging him into blindness — the ultimate darkness.

The motif of the “dangerous woman” as night is found far beyond Israel’s traditions. In Greek myth, Heracles loses his strength while in the service of the foreign queen Omphale, an episode often read as a symbolic diminishing of the hero’s power. In various Indo-European traditions, feminine figures personify shadow, dusk, or the consuming void that overtakes the day. Within this archetypal pattern, Delilah fits seamlessly — a shadow that slowly conquers the blazing hero.

Cross-Cultural Parallels

In Mesopotamia, the sun god Shamash made a daily descent into the underworld, disappearing from the world of the living. In Canaanite myth, Shapash guided divine and mortal affairs, moving between the realms of light and darkness. Samson’s capture and imprisonment echo this solar descent — the hero disappears into a Philistine “underworld” before a final return.

The Greek Heracles, like Samson, killed a lion with his bare hands, wielded improvised weapons, and met his downfall through the betrayal of a woman. Helios and Apollo, solar deities, were often depicted with radiant hair — another link to Samson’s symbolic “rays.”

Across cultures, hair often symbolizes life-force or divine energy. In Sumerian myth, Inanna’s beloved Dumuzi’s fate is bound to his physical vitality. In Greek legend, King Nisus loses his kingdom when his magical purple hair is cut. Samson’s hair-as-life motif belongs to this ancient storytelling tradition, echoing a pattern that stretches across civilizations and centuries.

Final Thoughts

The account of Samson in Judges is a striking example of why the Quran warns us not to assume that everything preserved in a religious canon is necessarily from God. While the Torah in its original form was divine revelation, the historical process of collecting, editing, and canonizing its content was driven by human hands. This means that alongside the word of God, there may also be narratives, embellishments, and cultural legends woven into the text — stories that reflect human imagination more than divine inspiration. The Quran cautions against such fabrications:

[6:93] Who is more evil than one who fabricates lies and attributes them to GOD, or says, “I have received divine inspiration,” when no such inspiration was given to him, or says, “I can write the same as GOD’s revelations”? If only you could see the transgressors at the time of death! The angels extend their hands to them, saying, “Let go of your souls. Today, you have incurred a shameful retribution for saying about GOD other than the truth, and for being too arrogant to accept His revelations.

In light of this, the Samson story — with its myth-like elements, symbolic patterns, and close parallels to older pagan hero tales — serves as a reminder to approach inherited scripture with discernment. It is possible to appreciate the moral and theological truths that endure in the Torah while also recognizing that not every word in the canon necessarily carries the stamp of divine authorship.