A German town hoped migration could turn its fortunes around. It was no panacea

By Riham Alkousaa

ALTENA, Germany (Reuters) -A decade ago, as Germany was grappling with an influx of more than a million migrants, the small town of Altena saw an opportunity to reverse years of population and economic decline.

The industrial town in Western Germany made national headlines in 2015 when it volunteered to take in 100 more migrants than required, becoming a model of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s pledge: “Wir schaffen das” – “We can do this.”

But while there have been benefits for both sides, three current and former town officials told Reuters migration wasn’t a panacea.

With the help of residents who mobilized to support the newcomers, many found homes and started contributing to the local economy, they told Reuters. But some moved on to bigger cities, which offer more work and education opportunities.

Others struggled to overcome language and cultural barriers, adding to rising welfare costs in a town with an aging population, officials said.

Now some local residents complain that the number of refugees and asylum seekers is getting too high. Recent election results show growing support for the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, fuelled by frustration over rising living costs, strained public finances and crumbling infrastructure.

“The glass is half full and half empty,” said Thomas Liebig, a migration researcher who contributed to an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report in 2018 on Altena’s efforts to integrate refugees. “Many refugees found jobs, but social cohesion still lags behind.”

WARM WELCOME

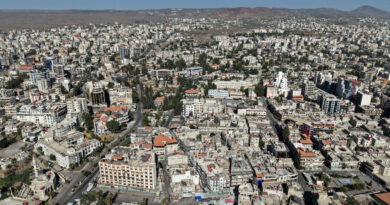

Nestled amid scenic wooded hills, Altena has been an industrial hub since the middle ages.

The riverside town describes itself as the birthplace of wire production. But local ironworks struggled to stay competitive in recent decades, wiping out a third of its jobs, the former mayor, Andreas Hollstein, told Reuters. Only the heavily automated steel wire sector survived.

By 2015, Altena was one of the fastest dwindling towns in western Germany with a population of around 17,000, just over half what it was in the 1970s, according to the World Bank.

The reduced tax base hurt the town’s finances, making it difficult to keep basic amenities open, officials said. Schools closed because there weren’t enough students to fill the classrooms.

When Hollstein suggested taking in more refugees and asylum seekers than the town’s allotment of 270 in 2015, there was broad support from local council members.

“Taking in families meant we could fill empty housing, reopen classrooms and bring new life to the town,” said Anette Wesemann, Altena’s integration commissioner. “It was a win-win.”

The town had already absorbed waves of migrant workers, including Italians and Turks recruited in the 1960s to staff its factories. So locals were accustomed to living alongside neighbours with different cultures and languages, Hollstein said.

Each refugee family or individual was paired with a local “kuemmerer”, or caregiver, to show them the ropes. Many residents volunteered to help, raising donations for care packages, furnishing homes for the new arrivals, accompanying them to medical appointments and helping with paperwork.

Leveraging the high vacancy rate, the town placed newcomers in apartments rather than a shelter. This helped integrate them into neighbourhoods, the OECD report said.

“For the children, we put dolls there,” recalled Dorothee Isenbeck, 81, one of the original volunteers. “There was a group of elderly men who decorated the apartments so beautifully, so they felt they were welcome.”

Data on the program is sketchy. Officials said they did not track how many migrants have come since 2015 or how they faired.

But by 2024, roughly half of the 100 additional arrivals that year were still living in Altena, Wesemann said. Most of the rest had moved to bigger cities, while a few Iraqis decided to return home, she said.

Among those who stayed is Humam al-Gburi, a 34-year-old Iraqi refugee who arrived by bus in October 2015. He said he had no idea what to expect, but the warm welcome eased his fears.

Lasting bonds were forged through the town’s integration program. A translator introduced him to Ursula Panke, an 85-year-old retired nurse he refers to as his “omi”, or grandmother.

Their friendship began when Gburi helped her set up an art exhibition. “He hung everything so precisely, so carefully,” she recalled, smiling.

She became a mentor, encouraging him to try different vocational courses until he found his calling. He now works as a nurse himself at a nearby orthopaedics and trauma clinic.

“In a big city, you’re just a number. Here, people know me. Uschi is my family,” Gburi said, using Panke’s nickname. “Family doesn’t mean blood — it’s the people who listen, who help, who stand by you.”

AfD’s RISE

Not everyone was so welcoming. Shortly after the first arrivals in 2015, a local firefighter set a building housing refugees on fire. No one was hurt in the arson attack.

Two years later, mayor Hollstein survived a knife attack by a man who cited his refugee policy as the motive.

With more migrants arriving every year, the mood among some residents started to sour.

“Hardly any German is spoken anymore. It’s all foreigners here,” Hannelore Wendler said outside a grocery store. “I have nothing against foreigners; they’re all people. But it’s too much.”

Anger over Merkel’s open-door policy toward migrants, many of them fleeing war and poverty in the Middle East and Africa, helped propel the rise of the AfD, which is now the country’s main opposition party.

Germany’s most populous state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), where Altena is located, is less conservative than eastern regions. But the AfD has been making inroads in the state’s small towns and rural areas, said Manfred Guellner, who heads the Forsa Institute for Social Research and Statistical Analysis, a leading German polling company.

Migration is not the main concern in NRW, he said, but rather rising inflation, job losses in the auto industry and a sense of economic decline.

“Only about half of AfD supporters even believe the party could govern better. People vote for it out of frustration with the others,” Guellner said.

The party won nearly 24% of the vote in Altena during February’s federal election, up from around 10% in 2017 and 2021.

“Altena is a prime example of failed integration and failed politics,” said Klaus Laatsch, the AfD parliamentary group leader in the Maerkischer Kreis district council, which includes Altena.

“All around us … it’s going downhill,” he said, citing rising energy costs, shuttered businesses, trash-strewn streets and inadequate transportation services. “Citizens experience these problems every day, and they see that past promises were never fulfilled.”

Still, the party has little visible presence in Altena. It has no office and is not fielding candidates in the town for the state’s municipal elections on Sept. 14.

Altena’s contributions toward the assimilation of refugees in Germany were recognised in 2017 with an award from the federal government.

But the population has continued to decline. By the end of 2024, there were just over 16,600 residents, 4% less than in 2015, according to figures from the state statistics office.

The town’s finances improved, though Hollstein said that had more to do with spending cuts, tax increases and a rebound in local steel processing than the relatively small number of migrants who chose to remain.

But even as some leave, others continue to arrive, officials said.

They are drawn by the town’s affordable housing and welcoming reputation, said a Syrian supermarket owner and two of her customers, who did not want their names published for fear of drawing unwanted attention.

After years of effort, some early volunteers are now stepping back, and finding replacements is becoming harder, Hollstein said.

But the town remains relatively unchanged, he said. “That’s positive. The newcomers live among us; their kids are in school; life goes on.”

Looking back, he remains convinced that Merkel was right.

“We can do this,” he said. “But critics are right too — Germany can’t absorb those numbers indefinitely.”

(Reporting by riham alkousa; editing by alexandra zavis)