Keep Zakat Sacred: A Right Of The Poor, Not A Political Tool

Imagine a masjid having the funds to uplift a family out of poverty, but bullying them instead. This is exactly what happened at one suburban masjid.

It was in an area full of families who bought homes and put their kids in school in a place where -by definition- they would not come in contact with poor people. Over time, a couple of families (think single mom, multiple kids, barely subsisting below the poverty line) would start attending regularly.

This is the type of situation where strong community leadership, and a strong grounding in the purpose of zakat, would lead people to realize they had more than enough zakat collection to literally take an entire family in their own community out of poverty. They could have bought them a place to live, put their kids through school, created a positive generational impact in the lineage of that family – and still had zakat funds leftover to fund their gym expansion.

Keep supporting MuslimMatters for the sake of Allah

Alhamdulillah, we’re at over 850 supporters. Help us get to 900 supporters this month. All it takes is a small gift from a reader like you to keep us going, for just $2 / month.

The Prophet (SAW) has taught us the best of deeds are those that done consistently, even if they are small.

Click here to support MuslimMatters with a monthly donation of $2 per month. Set it and collect blessings from Allah (swt) for the khayr you’re supporting without thinking about it.

Instead, they mistreated them and made them jump through hoops to get funds (which, even then, were not nearly enough). The very funds that are the right of the poor and belong to them.

Zakat is one of the five pillars of our deen, and stories like this show how far we’ve strayed from its purpose.

Historically, there have always been differences of opinion on how funds can be spent (I’m old enough to remember this 2007 article arguing for zakat to be given to dawah organizations creating controversy online).

More recently, the Fiqh Council of North America (FCNA) published a fatwa on the permissibility of donating zakat funds to political campaigns. It was published alongside a dissenting opinion of that fatwa.

I want to be clear that I have no intent (or qualification) to critique the ruling from a jurisprudential perspective. If you are interested in that, Imam Suhaib Webb has put together a short video series (Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3) that provides an explanation from a fiqh perspective as to why donating to political campaigns is not a legitimate use of zakat funds.

I do respect and recognize the need for this type of fatwa in the broader context of building a corpus of Islamic rulings in different times and places. No one ruling or piece of research is the finality of that topic. A ruling like this functions as something that other scholars can refer back to for critique or refinement.

I want to look at this ruling beyond the legalistic permissibility and more in context of a lack of leadership in how our community thinks about the institution of zakat.

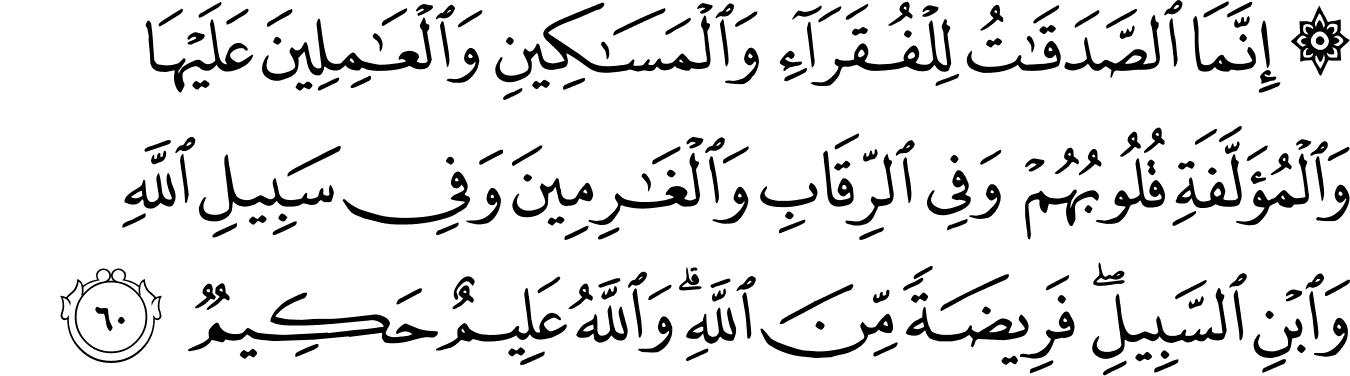

The core of this discussion centers on the ayah in Surah At-Taubah that lays out the categories of zakat: “Alms are meant only for the poor, the needy, those who administer them, those whose hearts need winning over, to free slaves and help those in debt, for God’s cause, and for travellers in need. This is ordained by God; God is all-knowing and wise.” [Surah At-Taubah: 9;60]

“Alms are meant only for the poor, the needy, those who administer them, those whose hearts need winning over, to free slaves and help those in debt, for God’s cause, and for travellers in need. This is ordained by God; God is all-knowing and wise.” [Surah At-Taubah: 9;60]

If you are unfamiliar with this ayah, I would recommend reading a quick explanation of it to get a basic grounding.

The core purpose of zakat is not disputed – it is a right of the poor upon the wealthy. Intuitively, we all understand this as the basic premise. And yet, the discussion our community has about zakat very rarely talks about the alleviation of poverty or uplifting the poor.

When I think back to discussions I have been privy to within a board or masjid setting, I would find community leaders talking about donating zakat funds in bulk to an Islamic organization, sending it overseas, or using it for masjid expenses and construction.

They would always hesitate to give to people locally, fearful that they might be taken advantage of. So they created city-wide databases to track how much a person had received so that they did not get too much. I have seen cases where people are exploited – forced to work manual labor jobs around the masjid for less than minimum wage, or cleaning the houses of the wealthy board members, just to get a small pittance of zakat support.

Then we get fatwas telling us we should be expanding who gets zakat – masjid construction projects, Islamic schools, Sunday schools, dawah organizations, and now, apparently, political lobbyists or candidates.

We find ways to strategize how to use zakat for almost everything except actually helping the poor.

The entirety of the zakat discussion that we have seems to talk about everything except the actual purpose of helping those in need. It is a discussion shaped by the perspectives of the wealthy – people who are insulated from the day-to-day realities of food insecurity, lack of housing, systemic poverty, and economic inequality.

This results from the mentality and culture pervasive in our American society. In a land where we are taught we can work hard to achieve anything, we are also implicitly taught that those who are less fortunate are simply not working hard enough, or deserve the situation they are in.

Instead of a love and reverence for the poor, we deride them. We see them as an inconvenience. Instead of empathizing with them, we want to write a check to a relief organization, maybe host a food drive with some good PR, and be done with it so we can go back to strategizing on more important issues like using zakat funds to build a new wing of Sunday school classrooms.

I recently came across an article painting the contrast between two different masjids in my city. The entire article is worth a read as it examines a number of important issues beyond the scope of this post. One quote particularly relevant to our context stood out:

“He argues that nurturing social services programs for the economically disadvantaged, like Masjid Al-Islam does in its South Dallas neighborhood, should be at the “heart” of Muslim community-building in Dallas, rather than consolidating wealth. He pointed out that the same racist forces that decimated Black communities in the United States were now uniting to target EPIC City. Without addressing the most oppressed among them, Muslims cannot consolidate their power. “Black American Muslims and the immigrant Muslims have not fully connected and united. We are not operating as an ummah at our full potential,” added Imam Abdul-Jami.”

This brings us back to the fatwa on using zakat funds for political causes. What purpose does it serve? Who is shaping that purpose? And why?

Had this been a fatwa about using general funds to fund a PAC, or influence politicians, there would be no objection. Why specifically zakat funds?

“The entirety of the zakat discussion that we have seems to talk about everything except the actual purpose of helping those in need.” [PC: Masjid Pogung Dalangang (unsplash)]

Who decides which political candidates can receive these funds?

How much are we going to assess a politician’s overall platform before giving them zakat? Are people supposed to take this fatwa and just pick political campaigns to give some of their zakat funds to?

What if a politician takes money from a Muslim group and then turns around and attacks them anyway?

How much do we need to donate before we can expect a tangible benefit to the community? For reference, the losing candidate in the 2024 Presidential election burned through $1.5 billion of campaign funds.

What if the funds end up in the hands of a politician who advocates for policies that further increase systemic poverty? Politicians who are in favor of eliminating social safety nets like food stamps?

How ironic would it be to dedicate a portion of our zakat money to a politician who ends up passing policies that systematically increase the number of people who need zakat to survive?

Are we only giving to candidates who are perhaps considering becoming Muslim? Or are we hiring people for a specific job?

Are political causes here meant to be quid pro quo? Are we guaranteeing that a politician will vote a certain way on a certain issue if they receive a certain amount of funding? Which votes are important enough to fund with zakat? What impact do they have on our community?

In short, it’s not clear what this fatwa is trying to accomplish, or how it should be implemented. And I understand that some will say the job of a jurist is to only establish the legal boundary. My response to that would be that a jurist issuing such a ruling without taking on the ground reality into account is doing a disservice and undermining the public’s trust in the institution of Islamic scholarship itself.

There is no blueprint showing a successful implementation of political advocacy by Muslims that justifies risking zakat funds. There are countless examples to the contrary – numerous White House Iftars where we fought for a ‘seat at the table’, Muslims ascending to higher ranks within the Biden administration, or Muslim physicians in the Dallas area privately hosting Greg Abbott in their homes to fundraise for him.

What, exactly, is the outcome of investing money into this type of political game? I am not saying it cannot be done, or even that we should not take part. Just do it with regular fundraising channels instead of zakat funds.

Rather, the more likely outcome is that it will pave the way to following the footsteps of politically aligned mega-churches that lose congregants due to their willful neglect of core teachings, such as caring for the poor. This, for me, is the most confusing part of the fatwa, as it quite literally appears to divert funds away from those who need it to survive, and instead line the pockets of corrupt actors who have no interest in Islam.

The Fiqh Council’s fatwa offers this justification:

“If we apply the rules with strict adherence to classical conditions (which, it should be noted, are largely ijtihādī in nature as well), this would weaken the practical functioning or aims of the Sharīʿah for this category, and essentially make this category null and void.”

In other words, if we do not find a way to identify a modern group of “those whose hearts are to be reconciled” (al-mu’allafah qulūbuhum), then we won’t be able to fulfill the injunction to give to people in this category.

The irony of this null and void framing is particularly striking given that the very same Fiqh Council had no problems whatsoever pressuring masjids all across America to adopt calculations for determining Ramadan and Eid, rendering the sunnah of physically sighting the moon and the duas related to it null and void.

When a fatwa like this is given with no context or a plan forward, it makes people lose faith in the leadership of the community. This discussion is compounded by recent revelations that an Islamic organization that raised $7 million for Gaza, diverted over $2 million to an individual for a completely unrelated cause unbeknownst to the donors.

Why is there not a focus to encourage people to utilize this category for other causes, such as food pantries, clinics, and other services in underserved areas?

There seems to be an underlying assumption that we’ve somehow ‘covered’ the primary purpose of zakat, and now we can move to other uses for it. Do any masjids or organizations collecting zakat have data showing how many families they have uplifted out of poverty? How many families in our masjid that were in need of zakat, got help, and now are in a position of being able to give zakat themselves?

Is anyone even paying attention to this – or do we simply not care?

It feels like we are numb to it, or we live lives where we can afford to be insulated from it. Then, when a politician attacks our masjids and organizations, we feel a visceral fear of what might happen to our community and want to do what we can to combat it.

Which is a perfectly fine sentiment. But let’s push ourselves to think more abundantly. Let’s find ways to use zakat more effectively for its primary purpose, and also raise other funds for other efforts.

For individuals in the position of giving zakat, it is imperative to exercise your own agency and take control of where your money is going. Be intentional about exactly what kinds of causes you want to support, and how best to support them. It may mean privately giving to families in need, or stepping back and giving to local organizations where you have more transparency regarding the work being done.

Zakat is not a light duty; it is one of the five major pillars on which our faith is built. Give it its proper and sacred due.

Related Reading (in addition to what is linked to in the article above)

[This article was first published here, where you can subscribe to receive more of the author’s content.]