Knowledge Over Power: Lessons from Solomon’s Court

A vast army marches through a valley—legions of humans, jinn, and birds mobilized under the command of Solomon, a king whose authority spans the visible and invisible worlds. The ground trembles beneath their advance. And then, from somewhere in the dust and chaos, a single ant cries out a warning to her colony: “Go into your homes, lest you get crushed by Solomon and his soldiers, without perceiving.”

Solomon acknowledges her concern.

The entire host pauses. Not because of a rival army or divine command, but because of one tiny creature’s knowledge of danger. In that moment, the balance of power shifts. The ant possesses no throne, no army, no status—only awareness. And that awareness reaches the king’s ear and alters the path of an entire army.

This scene, preserved in Sura 27 of the Quran, reveals a truth that cuts against the grain of how societies measure strength. Throughout history, we have admired those who wield power—whether through military might, political authority, or inherited status. Empires rise and fall on the strength of armies. Leaders command through force and position. Yet the Quran consistently shifts the lens, reminding us that true strength does not rest in armies, wealth, or position, but in knowledge. Power can coerce, but knowledge illuminates. Status can command, but knowledge directs the course of events.

He bestows wisdom upon whomever He chooses, and whoever attains wisdom, has attained a great bounty. Only those who possess intelligence will take heed. (2:269)

In the story of Solomon found in Surah 27, we encounter a series of striking illustrations of this principle. A humble ant, an observant bird, a strategic exchange with a foreign queen, and one endowed with knowledge of the book—each stands as a reminder that information and understanding can overturn the balance of power, where even kings and mighty jinn must yield. These narratives form an ascending arc, from the earthly to the transcendent, showing us that might and status alone do not determine the outcome of events.

Solomon’s high status, as presented in the Quran, lies not merely in his unprecedented dominion, but in his recognition that knowledge—whether from the smallest creature or the highest wisdom—demands his attention, humility, and response.

Solomon and the Ant: The Democracy of Truth

The scene that opens our exploration appears simple on the surface, yet it contains profound implications about power, knowledge, and accountability. Solomon was no ordinary king. The Quran tells us he inherited more than David’s throne—he inherited knowledge itself:

We endowed David and Solomon with knowledge, and they said, “Praise GOD for blessing us more than many of His believing servants.” Solomon was David’s heir. He said, “O people, we have been endowed with understanding the language of the birds, and all kinds of things have been bestowed upon us. This is indeed a real blessing.” Mobilized in the service of Solomon were his obedient soldiers of jinns and humans, as well as the birds; all at his disposal. (27:15-17)

This unique endowment fundamentally changed Solomon’s relationship to the world around him. He could understand the language of birds, the communication of ants, and the concerns of creatures great and small. But this gift was not simply a curiosity or entertainment—it was a burden of knowledge that created accountability. Solomon could no longer plead ignorance. He could not dismiss the thoughts and concerns of even the smallest creatures as irrelevant noise. Every voice he could understand became a voice he was responsible to hear and act upon.

So when his massive army—humans, jinn, and birds marching in formation—approached a valley of ants, and one solitary ant called out her warning, Solomon was confronted with a choice. The ant had no authority to command him. She possessed no weapon to threaten him. She held no political leverage. What she had was knowledge: an awareness of danger and the moral courage to sound the alarm.

“O you ants, go into your homes, lest you get crushed by Solomon and his soldiers, without perceiving.” (27:18)

Consider what this moment reveals. The ant does not accuse Solomon of malice. She says “without perceiving”—acknowledging that the destruction would be unintentional, collateral damage from forces too vast to notice her colony’s existence. Yet unintentional harm is still harm. The ant’s knowledge—her awareness of her colony’s vulnerability—becomes information that Solomon cannot unhear.

Here we see knowledge operating at its most fundamental level: as truth spoken without power behind it. The ant has no ability to enforce her will. She cannot stop the army. She can only speak what she knows and hope it reaches the right ears. And remarkably, it does.

Solomon’s response demonstrates why the Quran elevates him as an exemplar:

He smiled and laughed at her statement, and said, “My Lord, direct me to be appreciative of the blessings You have bestowed upon me and my parents, and to do the righteous works that please You. Admit me by Your mercy into the company of Your righteous servants.” (27:19)

He could have ignored her. His army could have marched on, the ants crushed beneath boots and hooves, a minor tragedy beneath the notice of history. Instead, Solomon smiled—not in mockery, but in recognition. He saw in that tiny creature a reminder of his own responsibility. His power was not his own to wield carelessly. His knowledge of her concern meant he was accountable for what happened next.

What makes this account so striking is its democratization of truth. In Solomon’s court, wisdom could come from anywhere—even from a creature without status, wealth, or might. The ant’s knowledge, humble and local though it was, possessed the authority to redirect an entire army. Power had to bend before truth, regardless of its source.

This stands in sharp contrast to how power typically operates. Rulers surrounded by yes-men, institutions that silence whistleblowers, systems that dismiss warnings from those deemed too small or insignificant to matter—these are the opposite of Solomon’s response. The ant reminds us that knowledge creates obligation. To know is to be responsible. And those who possess power cannot hide behind ignorance when truth has been spoken in their hearing.

The scene also reveals something about the nature of Solomon’s kingship. His greatness was not that he dominated all creatures, but that he remained attentive to all creatures. His strength was not in crushing opposition, but in recognizing wisdom wherever it appeared. The smile, the prayer of gratitude—these show a king who understood that his elevated position was a test, not a trophy.

In this first account, we see knowledge at its most accessible and most challenging form: truth spoken by the powerless to the powerful, changing the course of events not through force but through moral weight. The ant’s warning establishes the foundation of our thesis—that awareness, information, and understanding can shift the balance of power entirely, making even the mightiest accountable to the smallest voice of truth.

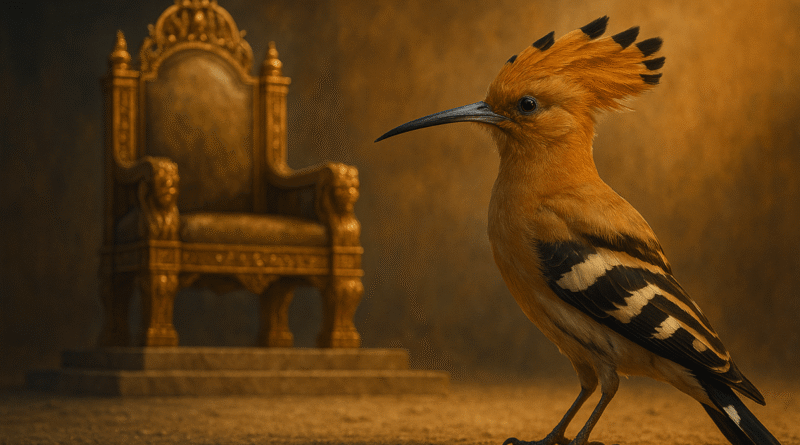

Solomon and the Hoopoe: Intelligence as Power

If the ant’s knowledge operated at the level of immediate, local awareness—a warning about physical danger—the hoopoe’s knowledge operates at an entirely different scale. Here we move from the personal to the geopolitical, from moral accountability to strategic intelligence. The hoopoe possessed information that could reshape the balance of power between kingdoms.

The account begins with Solomon conducting a roll call of his subjects. With dominion over humans, jinn, and birds, he expected order and full attendance. The inspection was not merely ceremonial—it was an exercise of authority, a reminder that every creature under his command was accountable to him. When he noticed that the hoopoe bird was missing, his reaction revealed the absolute nature of his power:

He inspected the birds, and noted: “Why do I not see the hoopoe? Why is he missing? I will punish him severely or sacrifice him, unless he gives me a good excuse.” (27:20–21)

This is not the gentle, smiling Solomon we saw with the ant. This is a king asserting his authority, making clear that absence without explanation is a capital offense. He could punish, banish, or execute. The threat was real and the power to carry it out unquestioned. In this moment, Solomon held every advantage: status, authority, the power of life and death.

Yet when the hoopoe returned, everything changed. The bird did not return with apologies or excuses. He returned with something far more valuable—information that Solomon, despite all his wisdom and prophetic insight, did not possess:

I have news that you do not have. I brought to you from Sheba, some important information. I found a woman ruling them, who is blessed with everything, and possesses a tremendous palace. I found her and her people prostrating before the sun, instead of GOD. The devil has adorned their works in their eyes, and has repulsed them from the path; consequently, they are not guided. (27:22–24)

Notice the hoopoe’s opening gambit: “I have news that you do not have.” This is a remarkable statement to make to a king who has just threatened your life. But the hoopoe understood something crucial—he possessed leverage. His intelligence about Sheba was not merely interesting gossip; it was strategically vital information about a wealthy, powerful kingdom engaged in what Solomon would consider grave religious error.

The hoopoe’s report was comprehensive and specific. He identified the ruler (a queen), assessed her resources (blessed with everything, possessing a tremendous palace), observed her people’s religious practices (prostrating to the sun), and offered an analysis of their spiritual condition (led astray by the devil, not guided). This was reconnaissance of the highest order—political, economic, and theological intelligence gathered and delivered with clarity.

In that moment, the power dynamic inverted completely. Solomon’s authority to execute the hoopoe became subordinate to his need for the information the hoopoe carried. If Solomon silenced or punished the bird, he would lose access to intelligence that could shape the course of events between kingdoms. His military strength, his royal status, and even his prophetic role were suddenly dependent on information held by a creature small and seemingly insignificant.

This is knowledge operating not as moral truth, but as strategic power. The hoopoe had ventured beyond Solomon’s borders and returned with intelligence that opened new possibilities. Solomon could now engage with the queen, attempt to guide her toward monotheism, and potentially bring an entire kingdom into proper worship. None of this would have been possible without the hoopoe’s initiative and observation.

What makes this account particularly instructive is that the hoopoe was not commanded to gather this intelligence. He was simply absent, presumably following his own curiosity or instinct. Yet his unsanctioned reconnaissance proved more valuable than his presence at roll call would have been. This suggests something profound about the nature of knowledge: it often comes from unexpected sources, from those who venture beyond established boundaries, from curiosity that operates outside the chain of command.

Solomon’s response to the hoopoe’s report also reveals his wisdom. He did not immediately accept the information at face value, nor did he dismiss it:

He said, “We will see if you told the truth, or if you are a liar. Take this letter from me to them, then watch for their response.” (27:27-28)

Solomon verified. He tested the intelligence. But the crucial point is that he took it seriously enough to act on it, sending a letter to the Queen of Sheba that would ultimately lead to her submission to God. The hoopoe’s information became the catalyst for a peaceful transformation of an entire kingdom—a far greater achievement than any military conquest could have accomplished.

Here we see knowledge elevated beyond local, immediate truth to strategic intelligence that shapes the relationships between nations. The hoopoe, lacking any conventional power, nevertheless possessed something that made him indispensable: information that the most powerful king on earth needed to hear. His knowledge protected him from execution and initiated a chain of events with far-reaching consequences.

The lesson is clear: those who possess information that others lack hold a form of power that can humble even kings. Solomon’s authority was real and vast, but it was not absolute. It was constrained by what he knew and did not know. The hoopoe’s intelligence filled a gap that armies could not fill and that prophetic wisdom alone had not revealed. In the hierarchy of power, knowledge proved itself essential and, in this moment, superior to the authority to command or kill.

Solomon’s Letter: The Ambiguity of Power and Wisdom

Between the hoopoe’s intelligence and Solomon’s ultimate demonstration of divine knowledge lies a fascinating exchange that reveals how profoundly different the language of power is from the language of wisdom. When Solomon received confirmation of the hoopoe’s report, he sent a letter to the Queen of Sheba—a message that would be understood one way by those who think in terms of conventional power, but would manifest in an entirely different manner through divine wisdom.

The Queen received Solomon’s letter and shared it with her advisers:

She said, “O my advisers, I have received an honorable letter. It is from Solomon, and it is, ‘In the name of GOD, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.’ “Proclaiming: ‘Do not be arrogant; come to me as submitters.’”(27:29-31)

The letter was brief and direct: a call to submit to God, framed as a command from a powerful king. The Queen recognized it as significant enough to convene her council. Her advisers responded in the only language they knew—the language of military power:

They said, “We possess the power, we possess the fighting skills, and the ultimate command is in your hand. You decide what to do.” (27:33)

Their answer revealed their worldview. They assessed the situation through the lens of force: we have armies, we have capability, we can fight if necessary. The Queen, however, demonstrated greater wisdom than her advisers. She understood how power typically operates:

She said, “The kings corrupt any land they invade, and subjugate its dignified people. This is what they usually do. I am sending a gift to them; let us see what the messengers come back with.” (27:34-35)

Her analysis was astute. Kings conquer through invasion, corrupt through occupation, and humiliate through subjugation. This is the pattern of worldly power. So she attempted diplomacy—sending a gift to test Solomon’s intentions, to see if he could be appeased or negotiated with like other rulers.

Solomon’s response was unequivocal:

When the hoopoe returned to Solomon (he told him the news), and he responded (to Sheba’s people): “Are you giving me money? What GOD has given me is far better than what He has given you. You are the ones to rejoice in such gifts.” (To the hoopoe, he said,) “Go back to them (and let them know that) we will come to them with forces they cannot imagine. We will evict them, humiliated and debased.” (27:36-37)

This is where the brilliance of Solomon’s strategy becomes apparent. His words—”we will come to them with forces they cannot imagine, we will evict them, humiliated and debased”—sound unmistakably like a declaration of war. Any ruler, any military adviser, any person thinking in terms of conventional power would hear this as a threat of invasion, conquest, and subjugation. Solomon knew this. He understood exactly how his message would be perceived by those who measure strength in armies and assess threats through the lens of military force.

Yet Solomon meant something entirely different.

He did come to them with forces they could not imagine—not human armies, but those of jinns. Beings of supernatural power, invisible to ordinary perception, capable of feats beyond human comprehension. The Queen and her advisers, for all their military capability, had no framework for understanding or resisting such forces. Their “power” and “fighting skills” were irrelevant against servants who could transcend the laws of nature itself.

He did evict them—not from their land, but from their palace. The very seat of the Queen’s authority, the symbol of her sovereignty and wealth, was removed from Sheba and placed before Solomon’s throne. This was not military occupation; it was a demonstration that rendered military resistance meaningless. What use are armies when your palace can vanish in an instant?

He did humiliate them—not through violence or subjugation, but through a transformation that exposed the limits of their understanding. When the Queen arrived and saw her palace before her, Solomon had it subtly altered to test her perception. The humiliation was not of conquest but of recognition—the realization that everything she had built her power upon could be moved, changed, and transcended by forces beyond her control or comprehension.

This is knowledge operating as strategic ambiguity. Solomon spoke in the language his audience would understand—the language of military threat—while intending to demonstrate something they could not yet conceive: that divine wisdom renders conventional power obsolete. He fulfilled every word of his message, but not in the manner they expected. The threat was real, but it was not the threat they prepared for.

The Queen’s advisers had counseled from a position of confidence in their military strength. They believed they possessed adequate power to resist. But they were preparing for the wrong kind of confrontation. You cannot defend against knowledge with swords. You cannot fortify against wisdom with walls. The forces Solomon commanded operated on a plane entirely different from the one where military power has meaning.

What makes this exchange so instructive is that Solomon could have invaded Sheba conventionally. He commanded vast armies of humans, jinn, and birds. He could have conquered through force, occupied through military might, and ruled through fear. That is what the Queen expected, what her advisers prepared for, what history had taught them to anticipate from powerful kings.

Instead, Solomon chose demonstration over destruction. He used his knowledge—his understanding of divine power, his command over forces beyond nature—to render military confrontation unnecessary. The Queen was not defeated; she was enlightened. She came to Solomon not as a conquered subject but as one who recognized the futility of resisting truth. Her submission was not forced through violence but inspired through the undeniable reality of what she witnessed.

This section of the narrative bridges our earlier accounts and the climactic demonstration to come. The hoopoe provided intelligence about a powerful kingdom engaged in false worship. Solomon’s letter established contact and declared his intentions. The Queen’s response showed conventional wisdom attempting to navigate the situation through familiar frameworks of power and diplomacy. And Solomon’s reply, deliberately couched in language that would be misunderstood, set the stage for a revelation that would transcend every expectation.

The lesson here is subtle but profound: knowledge allows for strategies that power cannot conceive. Solomon could operate on multiple levels simultaneously—appearing to threaten while actually planning to enlighten, seeming to prepare for war while orchestrating a demonstration of divine truth. Those who possess only power are limited to power’s vocabulary and power’s methods. Those who possess knowledge can choose when and how to reveal it, can craft messages with layers of meaning, can accomplish their objectives through means their opponents cannot anticipate or counter.

In the end, Solomon’s “forces they cannot imagine” were not merely jinn and supernatural capabilities. The true force they could not imagine was the power of knowledge itself—the ability to accomplish objectives without violence, to transform understanding without conquest, to bring a queen and her kingdom to submission not through subjugation but through undeniable demonstration of truth.

The One with Knowledge of the Book: Divine Wisdom Transcendent

We have seen knowledge operate as moral awareness in the ant, as strategic intelligence in the hoopoe, and as multi-layered communication in Solomon’s letter to the Queen of Sheba. Now we encounter knowledge in its most exalted form—wisdom that transcends the natural laws of space, time, and physical capability. This is the climax of our ascending arc, where the superiority of knowledge over mere power becomes undeniable and spectacular.

The account follows Solomon’s engagement with the Queen of Sheba. After the hoopoe’s intelligence proved accurate and Solomon’s letter prompted her journey to his kingdom, he decided to make a demonstration that would leave no doubt about the power of faith and divine wisdom. In a display of royal command, he posed a challenge to his assembled court:

He said, “O you elders, which of you can bring me her mansion, before they arrive here as submitters?” (27:38)

This was no small request. Solomon was asking for the Queen’s palace—not a token or symbol, but the actual structure—to be transported from Sheba to his court before her arrival. It was a challenge that tested the limits of what his mighty subjects could accomplish.

The first to answer was not a human but an afrit, a mighty jinn known for supernatural strength and speed. These beings, commanded by Solomon, possessed powers far beyond mortal capability. The afrit’s boast reflected confidence in raw might:

One afrit from the jinns said, “I can bring it to you before you stand up. I am powerful enough to do this.” (27:39)

On the surface, this seems like an impressive offer. “Before you stand up” suggests that the task could be completed within a negligible amount of time. By making such a grandiose claim, the afrit was declaring his strength, his speed, his ability to accomplish what would be impossible for any human. For a creature of such power to volunteer himself for this task should have been sufficient. After all, who could do better than that?

Yet the afrit’s offer, impressive as it was, rested entirely on force—the ability to physically transport the palace through supernatural strength and speed. It was power in its most direct form: might applied to matter. The afrit was offering to solve the problem the way power typically solves problems—through the application of superior force.

But then another voice emerged from Solomon’s court:

The one who possessed knowledge from the book said, “I can bring it to you in the blink of your eye.” When he saw it settled in front of him, he said, “This is a blessing from my Lord, whereby He tests me, to show whether I am appreciative or unappreciative. Whoever is appreciative is appreciative for his own good, and if one turns unappreciative, then my Lord is in no need for him, Most Honorable.” (27:40)

The contrast is stark and deliberate. Where the afrit offered hours, this figure offered an instant. Where the afrit relied on physical power, this individual wielded knowledge—specifically, knowledge derived from a book. The palace materialized not through the exertion of might but through the application of wisdom aligned with God’s will.

Who was this person? The Quran does not name him, referring to him only as “the one who possessed knowledge from the book.” This ambiguity itself is instructive—what matters is not his identity or status, but the source of his capability. He was not powerful in the conventional sense. He commanded no armies, possessed no supernatural strength like the jinn, held no royal authority. What he possessed was understanding—knowledge of divine principles that, when applied, could accomplish what raw power could not.

The term “knowledge from the book” suggests something profound about the nature of this wisdom. This was not merely intellectual information or strategic intelligence. This was knowledge rooted in some form of divine revelation, understanding that aligned human will with the fundamental laws of creation as established by God. When such knowledge is wielded with faith and proper intention, it becomes a force that transcends physical limitations entirely.

The instantaneous nature of the accomplishment deserves emphasis. “In the blink of your eye”—there was no process, no visible exertion, no journey through space. The palace simply appeared, fully intact, transported across vast distance in literally no time at all. This was not a refinement of the afrit’s method; it was a completely different order of operation. The afrit would have used time and force. The one with knowledge collapsed both, demonstrating that divine wisdom operates outside the constraints that bind even supernatural power.

Solomon’s immediate response to this miracle is equally telling. He did not congratulate the man or marvel at the palace. Instead, he turned to gratitude:

“This is a blessing from my Lord, whereby He tests me, to show whether I am appreciative or unappreciative.”

Solomon recognized what had just occurred. This was not merely a useful trick or a display of human achievement. It was a demonstration that knowledge aligned with God—true wisdom—surpasses every other form of power. The test was not whether Solomon could command such a feat, but whether he would recognize its source and respond with appropriate humility and gratitude.

The one with knowledge of the book also demonstrated this humility. He did not claim credit or boast of his ability. He immediately attributed the blessing to God and framed it as a test of his own character. This stands in sharp contrast to how power typically behaves. Might tends toward pride; it celebrates itself, demands recognition, builds monuments to its own achievements. But knowledge, when it is true and aligned with divine wisdom, points beyond itself to its source.

Even Solomon, who commanded armies of humans, jinn, and birds, who possessed wisdom and prophetic insight, who could understand the communication of various creatures—even he bore witness that knowledge derived from God’s revelation surpasses all earthly and supernatural might. The afrit’s power was genuine and impressive, but it was still bound by the mechanics of force and time. Divine knowledge operates in an entirely different dimension, rendering conventional power, no matter how great, relatively insignificant by comparison.

This is the culmination of the Quran’s message about knowledge and power. Might can accomplish much, but it is always working within limits. Knowledge—especially knowledge aligned with divine truth—can transcend those limits entirely. The lesson is not that physical power is worthless, but that it is ultimately subordinate to a higher order of understanding. In the final analysis, wisdom guided by God eclipses even the strength of jinn.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Listening King

Across these encounters, the Quran presents Solomon not merely as a king of unrivaled authority, but as a figure constantly humbled and elevated by knowledge. An ant with a warning, a hoopoe with intelligence, a queen who required enlightenment rather than conquest, and a man endowed with knowledge of the book—all stand as witnesses to a singular truth: might and status alone do not determine the outcome of events.

Solomon’s armies were vast, his throne unmatched, his command over jinn and nature extraordinary. Yet none of these proved ultimate. Time and again, the decisive factor was knowledge in its various forms: the moral awareness that redirected his armies, the strategic intelligence that opened diplomatic possibilities, the wisdom to communicate on multiple levels simultaneously, and the divine understanding that transcended physical laws entirely. Each encounter reinforced the same principle—knowledge is not only superior to force, it creates accountability and enables strategies that power alone cannot conceive.

What distinguishes Solomon in the Quran is not that he towered over creation with armies and dominion, but that he remained attentive to wisdom regardless of its source. He smiled at the ant’s concern, recognizing truth in the smallest voice. He stayed his hand when the hoopoe returned with information, understanding that intelligence could be more valuable than discipline. He spoke to the Queen of Sheba in language she would misunderstand, knowing that demonstration would prove more transformative than explanation. And he bore witness when knowledge of the Book accomplished what even jinn could not, acknowledging that divine wisdom operates in dimensions beyond conventional power.

This attentiveness was itself a form of knowledge—the understanding that wisdom can emerge from anywhere and must be honored wherever it appears. Solomon’s gift of understanding the speech of all creatures was not merely a curiosity; it was a burden of accountability. He could not plead ignorance. Every voice he could understand became a voice he was responsible to hear and act upon.

The progression of these accounts reveals something profound about the nature of knowledge itself. It begins with immediate, local truth—the ant’s warning about physical danger. It escalates to strategic intelligence that shapes relationships between nations. It manifests as communication that operates on multiple levels, speaking in familiar terms while preparing unprecedented demonstrations. And it culminates in divine wisdom that renders the impossible routine, collapsing space and time through understanding aligned with God’s will.

At each level, knowledge proved itself not as a complement to power but as something categorically superior. The ant had no army, yet her awareness altered the path of thousands. The hoopoe possessed no authority, yet his intelligence initiated the transformation of a kingdom. Solomon wielded tremendous power, yet he chose demonstration over destruction, enlightenment over conquest. And the one with knowledge of the Book accomplished in an instant what the mightiest jinn would require time and force to achieve—if they could achieve it at all.

This is why the Quran returns again and again to the theme of knowledge as the highest bounty:

He bestows wisdom upon whomever He chooses, and whoever attains wisdom, has attained a great bounty. Only those who possess intelligence will take heed. (2:269)

Solomon’s story is not ultimately about his vast dominion or his supernatural servants. It is about his recognition that true strength lies in wisdom, that genuine authority comes from understanding, and that lasting influence flows from knowledge rather than coercion. His legacy is not one of conquest but of discernment—the ability to recognize truth whether it comes from an ant, a bird, a foreign queen, or one with knowledge of a book.

In our own age, when power still dazzles and might still commands attention, Solomon’s encounters offer a corrective lens. We live in a world where information shapes economies, where understanding drives innovation, where knowledge can topple governments and build new ones. Yet we often still measure strength in the old ways—military force, political authority, accumulated wealth. The Quran reminds us that these forms of power, impressive as they may be, remain subordinate to something more fundamental.

Knowledge illuminates where power obscures. Understanding redirects where force merely compels. Wisdom transforms where might only conquers. And those who possess knowledge aligned with truth—whether they are as small as an ant or as exalted as a prophet—hold a form of power that can humble kings and reshape the course of history.

Solomon smiled at the ant. He listened to the hoopoe. He engaged the Queen with strategic wisdom. He acknowledged the one with knowledge of the book. In each case, he demonstrated that greatness lies not in the exercise of power over others, but in the recognition of truth from any source and the humility to act upon it.

The lesson remains timeless and urgent: might can conquer, but only knowledge can guide. Power can coerce, but only wisdom can transform. Status can command, but only understanding can lead us toward truth.

…We exalt whomever we choose to higher ranks. Above every knowledgeable one, there is one who is even more knowledgeable. (12:76)

In the end, Solomon’s greatest strength was not his armies or his throne. It was his willingness to be taught—by creatures great and small, by divine revelation and mortal insight, by the spectacular and the subtle. That willingness, that openness to knowledge regardless of its source, is the true mark of wisdom. And it is a lesson that transcends time, culture, and circumstance, speaking as clearly to us today as it did to Solomon’s court millennia ago.