Sunni Apologist Hadith Fragment (AP 259) Dishonesty

In a recent debate with Sunnis on Discord, some individuals cited a scholarly paper to claim proof of hadith manuscripts from the first century Hijri. In their typical fashion, rather than sending a link to the article, they only sent a screenshot of the article’s first page, underlining a single sentence:

“The date of this text, based on paleography, can be placed in the first two Islamic centuries (7th–8th centuries C.E.).”

From this, they triumphantly concluded that this was definitive proof of written hadith from the first century. However, this selective citation represents a profound misunderstanding—or deliberate misrepresentation—of the scholarly evidence, making it appear as if the article says something fundamentally different from its own conclusion regarding the dating of the text.

The Scholar’s Actual Conclusion

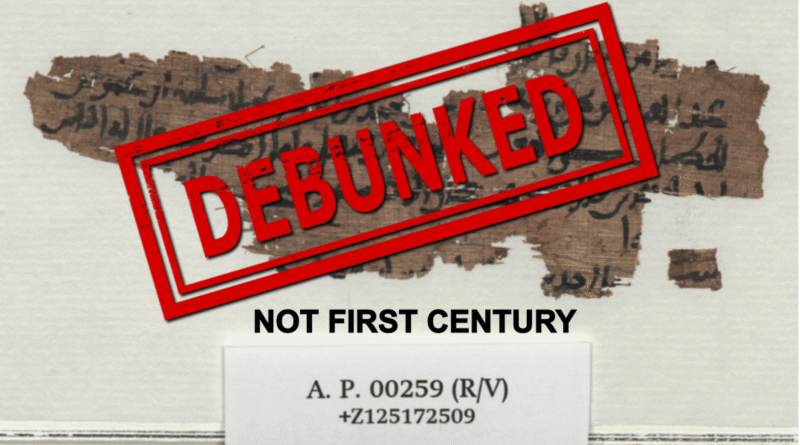

The paper in question is “A Ḥadīth Fragment on Papyrus” By Petra M. Sijpesteijn, Published in Islam 92, no. 2 (2015): 321-331. The fragment is designated as A.P. 00259 (R/V), and when we examine the full study rather than a decontextualized sentence, the evidence points in an entirely different direction.

The person sharing this screenshot highlighted and underlined this one sentence but failed to share the rest of the article, which would have undermined their entire argument. Far from supporting claims of first-century dating, Sijpesteijn explicitly states her conclusion, “The papyrus can roughly be dated to the second/eighth-early third/ninth century.”

“The papyrus can roughly be dated to the second/eighth-early third/ninth century on the basis of the script used on both sides of the papyrus and the form in which the account is presented. Most literary fragments of ḥadīths and other literary texts preserved on papyrus edited by Nabia Abbott were dated by her to the early third/ninth century. These all formed part of codices. The third/ninth century is also the date given by the editors to the two complete ḥadīth collections preserved in a papyrus codex and a scroll.”

The Isnād Reveals Source Cannot Be First Century

The hadith fragment contains a complete chain of transmission (isnād) that reads:

Suwayd b. ʿAbd al-ʿazīz → yaḥyā b. Saʿīd → muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm → abū salama →umar b. al-khaṭṭāb

From this, we can see that there are five transmitters in this chain, excluding the person who actually wrote this Hadith. This is the typical length of chain that we find in books like Sahih Bukhari (d. 256 AH / 870 CE), which dates back to the third century.

Sijpesteijn provides the death dates for these transmitters:

- Suwayd b. Iraabd al-Oa'czz (d. 167/783–4 or 194/809–10)

- Yaḥya b. Sʿad al-Anṣāre (d. 143/760–1)

- Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm al-taymī (d. 120/738)

- Abū Salama b. ʿBd al-Raḥmān (d. 94/713–4 or 104/722–3)

- ʿMar b. al-khaṭṭāb (d. 23/644)

The first transmitter in the chain, Suwayd b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, died either in 783 or 810 CE—well into the second Islamic century, during the Abbasid period. This isnād alone makes it impossible for the papyrus to be a “first-century hadith manuscript.”

Understanding Paleographic Dating

The misunderstood sentence about “first two Islamic centuries” refers specifically to paleographic analysis—the study of handwriting styles. Sijpesteijn uses this dating method to establish an upper boundary: the writing style indicates the text cannot be later than the 8th century. This paleographic assessment serves to prevent dating the text beyond a certain chronological limit, not to argue for first-century origins.

However, paleography alone cannot determine how early a text might be; for that, we need internal evidence. The isnād provides that internal evidence, anchoring the text to the late 8th or early 9th century when the last transmitter in the chain would have been active.

Sijpesteijn further notes that this papyrus represents “an informal recording of some ḥadīths for personal or educational use” rather than a formal manuscript tradition. She explains:

“Instead what we seem to be dealing with here is an informal recording of some ḥadīths for personal or educational use. The sources discuss how such personal notes with whole or partial ḥadīths were used by transmitters as aide-mémoires and for training purposes.”

This informal, note-taking format fits perfectly with the 8th-9th century period when hadith collections were being systematically compiled and organized.

The Pattern of Misrepresentation

This incident reveals a troubling pattern in some apologetic circles: the selective citation of scholarly evidence to support predetermined conclusions. By highlighting only the paleographic reference while concealing the isnād evidence and the scholar’s actual conclusions, the Discord user fundamentally misrepresented the academic findings.

Such selective quotation is not merely intellectually dishonest; it betrays a lack of confidence in the very tradition being defended. If hadith literature truly possessed the historical reliability its proponents claim, there would be no need for such distortion of evidence.

The Qur’an reminds us of our obligation to truth and justice:

[4:135] O you who believe, you shall be absolutely equitable, and observe GOD, when you serve as witnesses, even against yourselves, or your parents, or your relatives. Whether the accused is rich or poor, GOD takes care of both. Therefore, do not be biased by your personal wishes. If you deviate or disregard (this commandment), then GOD is fully Cognizant of everything you do.