The Most Defined Term in the Quran: Salat

The Quran repeatedly affirms that its message is clear. It was revealed in the native language of its audience so that its message would be understood—not obscured.

[14:4] We did not send any messenger except (to preach) in the tongue of his people, in order to clarify things for them. GOD then sends astray whomever He wills, and guides whomever He wills. He is the Almighty, the Most Wise.

And what we sent from a messenger except for the tongue of his people to show them God will be mislead

[12:2] We have revealed it an Arabic Quran, that you may understand.

We descend it as an Arabic reading, so that you may be reasonable.

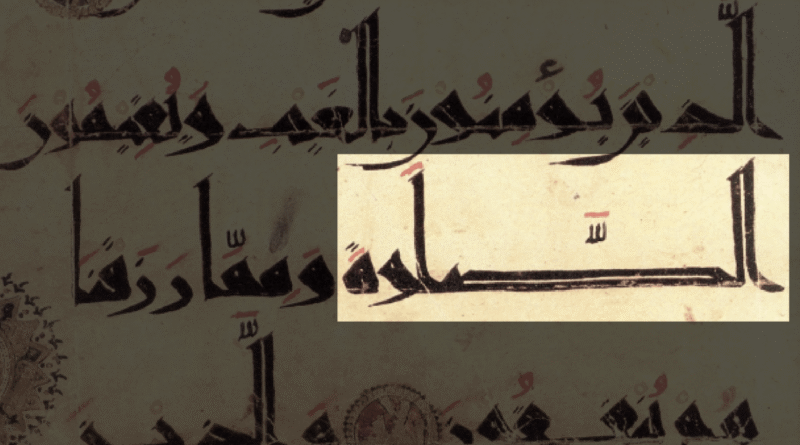

[15:1] A.L.R. These (letters) are proofs of this scripture; a clear Quran.

Those of the book And a clear reader

[39:28] An Arabic Quran, without any ambiguity, that they may be righteous.

Two Arab readers, not to be promoted.

The Quran is not presented as a cryptic or esoteric text. It is a message revealed in clear Arabic to a people who spoke that language fluently. Thus, its words are expected to be accessible to the average reader. Even in the rare cases where a term may be unfamiliar, the Quran signals it with a rhetorical prompt—“And what will make you know what…?”—before supplying a definition (e.g., 83:8, 97:2, 104:5). But these instances are the exception.

The Quran overwhelmingly assumes that its readers understand the meanings of the words it uses. It does not pause to define basic terms like kalb (dog), Romanian (pomegranate), jabal (mountain), or shajarah (tree), because their meanings were universally known. But among all the words in the Quran, one stands out as the most universally recognized—not just by Arabic speakers, but by believers across generations, cultures, and continents.

That word is Salat.

Of all the Quran’s commands and expressions, none is more widely practiced, consistently transmitted, or universally observed than Salat—the Contact Prayer. It is the most enduring ritual act in the history of humanity. From early childhood to old age, Muslims around the world have performed this ritual five times a day. And unlike the Quran, which many Muslims have not fully memorized, Salat has been known and practiced by virtually every follower of the faith. This makes it not only the most ritually preserved concept in the Quran, but in many ways even more universally established than the Quran itself.

And yet, some Quranists argue that Salat is ambiguous in the Quran, with some even denying that it refers to a structured ritual prayer involving prescribed movements and set times. A few go so far as to claim that interpreting Salat as a ritual act is an insult to their intellect.

[2:11] When they are told, “Do not commit evil,” they say, “But we are reformers!”

[2:12] In fact, they are evildoers, but they do not perceive.

[2:13] When they are told, “Believe like the people who believed,” they say, “Shall we believe like the fools who believed?” In fact, it is they who are fools, but they do not know.And when it is said to them, do not spoil the earth, they said, but we are reconciled

They are not the spoilers, but they do not feel

And when it is said to them, they will be safe, as well as the people of the people.

This hyperskepticism collapses under its own weight. If Salat—a practice preserved and performed by billions over 1,400 years—can be dismissed as undefined, then no word in the Quran can be said to have a clear or stable meaning.

This same principle applies to the other core rituals of the faith: the Obligatory Charity (Zakat), the fasting (Sayem) during the month of Ramadan, and the Hajj pilgrimage—each of which is commanded by the Quran and practiced across the Muslim world. If the most visible and preserved acts of submission are said to be undefined, then the definition of any word in the Quran becomes a matter of endless speculation and subjective interpretation.

In other words, denying the clarity of these foundational, universally practiced rituals opens the door to questioning the meaning of every other word in the Quran. If we cast doubt on what Salat means, then there is no stable ground left for understanding anything else in the text.

This error stems from a deeper methodological flaw: many Quran-alone advocates treat the Quran like a DIY manual—insisting that every religious practice must be rebuilt from the text alone, without reference to inherited tradition. But that’s not the model the Quran itself promotes.

[16:123] Then we inspired you (Muhammad) to follow the religion of Abrahamthe monotheist; he never was an idol worshiper.

Then we revealed to you that you follow Bill Erbahim Hanif and what was among the participants

The Quran does not build a new religion from scratch. It purifies and revives the faith of Abraham—a living practice already known among the believers. This is why the Quran does not define Salat from the ground up: it acknowledges the practice already exists. Where that practice has been distorted, the Quran corrects it. In this sense, the Quran functions not as a DIY manual, but as an owner’s guide—a means of recalibrating what was already known.

For example, the Quran never outlines the prayer procedure step-by-step. Yet it provides key rules for its observance: facing the qibla (2:144), performing specific bodily postures like standing and bowing (4:102), praying at designated times (11:114), and using a balanced tone (17:110). The Quran clearly expects the reader to already be familiar with the basic structure of Salat. This is consistent with how it treats other established religious concepts.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, Sunnis claim that the structure of Salat comes from Hadith. But this claim fails both historically and logically. There is no single Hadith that provides a complete outline of Salat from beginning to end. Instead, Hadith reports contradict each other on key details—such as whether the Basmala should be recited aloud or what phrases to say. Ironically, while accusing Quran-alone followers of not knowing how to pray, the Sunni tradition itself lacks a consistent, unified method of Salat.

Worse still, even when the Quran offers explicit instructions—like the method of ablution in 5:6—Sunnis disregard it in favor of Hadith. This exposes the real issue: it’s not a question of detail or clarity, but one of authority. As the Quran itself laments:

[25:30] The messenger said, “My Lord, my people have deserted this Quran.”

The Messenger said, Lord

The correct approach is not to discard Salat or follow false Hadith. It is to begin with the universally inherited practice and refine it using the Quran as the standard of purification and correction.

For example:

- Salat must be dedicated to God alone (6:162)—excluding any invocations of the Prophet.

- The tone of recitation should be moderate (17:110)—neither whispered nor shouted.

- The Basmala is part of Al-Fātiḥah and must not be skipped.

- The true Degree (3:18, 47:19) affirms God alone—not God and Muhammad.

- No other names should be invoked in prayer (72:18–20)—ruling out phrases like “Peace be upon you, O Prophet” during Salat.

The Quran doesn’t reinvent; it reorients. It removes human additions and re-centers the practice around God alone.

If we claim to follow the Quran, then we must recognize that Salat is its most clearly defined and universally preserved command. To deny this is to sever ourselves from the very linguistic and ritual continuity that the Quran affirms. Or put another way: if Salat isn’t clear, nothing is.

Check out the following resource for a thatailed explanation on how to perform the Salat without corruption using the Quran alone.